- Rifles

- Optics

- Ammo

- Hunting

- News

- Target shooting

- Gear

- Competitions

- More

-

-

More

-

- No posts selected.

-

-

-

-

Save on shop price when you subscribe to Rifle Shooter. Pay just £4.49 per issue – 44% cheaper than buying in-store. Subscribe here

Reading the wind

Long-range misses often come down to wind. Mark Ripley explains how to judge this unseen force across distances and techniques to read it accurately for successful shots

The wind: your greatest long-range enemy

The biggest cause of a miss at longer ranges—assuming it’s not simply bad shooting—is failing to allow for wind properly. The easiest way to imagine wind is to think of it as water. This helps you understand how it flows around obstacles like woods or buildings and follows the terrain’s shape.

On open, flat ground, the wind will usually be steady. But in a valley, it will follow the natural channel. If it hits an object, it splits around it.

Understanding what the wind is doing is easier if you’re physically at the location. However, we also need to know what it’s doing at the target—and everywhere in between. That’s the real challenge for long-range shooters. It’s especially tough for hunters who often only get one shot.

Reading the wind at your firing point

Let’s start with methods to read the wind at your firing position. The simplest and most accurate way is to buy a wind meter. Basic ones cost as little as £10. A more accurate model, like the Skywatch, costs around £30. At the top end is the Kestrel range. These give a host of environmental readings and even provide ballistic corrections to dial into your scope.

What direction is the wind blowing?

Before worrying about speed, you first need to determine direction. At your position, this is easy. You’ll feel most breezes on your face. Tossing a little grass in the air also works.

A small bottle of kids’ bubbles is handy for seeing wind direction. You can watch the bubbles drift and see swirls or shifts. Stalkers often use bottles of fine powder for this same purpose.

Estimating Wind Speed

Next, you’ll need to gauge wind direction out to your target. This is harder. Look for clues like moving grass, bending branches, or drifting smoke.

If you’re confident about direction, it’s time to estimate speed. An old method is to drop a handkerchief or bit of paper from shoulder height. Point to where it lands and estimate the angle from your body to your arm. Divide that angle by four to get an approximate wind speed in mph. For example, a 40° angle gives you 10 mph.

This only works at your location and isn’t very accurate—but it’s better than nothing if your wind meter’s dead or still in the truck.

Reading the wind down range

Reading wind at your position is one thing. But what about further out?

On a shooting range, flags along the course help you judge wind angles precisely. And in the field, you don’t have that luxury. But there’s another tool available: mirage.

Using mirage to gauge wind

Mirage isn’t just for hot sunny days. You can often spot subtle heat rising from the ground, even in cooler weather.

Pick a spot at least halfway to the target—perhaps a flat patch, hill brow, or open surface. Using a high-magnification spotting scope (or your riflescope), turn it slightly out of focus. Look for wavy lines or shimmering across the surface.

If you’ve ever seen the shimmer above a hot tarmac road, you’ll recognise the effect.

Interpreting mirage angles

I often film my long-range shooting for my YouTube channel—260rips. I use my camcorder’s zoom to watch the mirage down range. Once you spot the shimmer, interpret the wind based on the angle of the rising waves.

Think of these waves like rising smoke. If they go straight up, it’s called a “boiling mirage.” This means no wind, or that wind is blowing in line with the bullet’s path.

Reading mirage accurately takes practice, but it’s worth learning.

Here’s a simple guide:

-

A 60° lean = 1–3 mph crosswind

-

A 45° lean = 4–7 mph

-

Horizontal waves = 8–12 mph

Above that, mirage reading becomes unreliable.

Putting it all into practice

Try to combine all the visual clues—plus wind readings at your firing point—to make a solid correction.

When I’m out long-range varminting, I find a spot with a good view of likely targets. I set up my gear, load the rifle, then assess the wind’s direction and strength.

Once I’ve picked a target, I dial for the wind at its most consistent speed. For instance, with a wind varying between 8–12 mph, I’ll dial for 10 mph. Then I hold off slightly, based on what I feel or wait for the wind to stabilise before taking the shot.

Final thoughts

When shooting at range, wind is your biggest enemy—assuming you’ve already accounted for bullet drop. Hopefully, this has made you more aware of how to deal with it.

For target shooting or when taking a long shot on a wounded animal, dial for the wind speed at your position. That’s the wind with the greatest influence on your bullet. Even a slight deviation will have magnified effects down range.

Hold your wind meter with its side facing the target and the back into the wind. This gives you a rough speed, even for angled winds.

It’s a crude technique, but it gets you close. Then walk follow-up shots onto target by watching for splash and adjusting your hold.

This method is only really suitable for targets or hasty shots on injured animals. For game at extended ranges, never guess. Only shoot when you can make a calculated, confident shot for a clean kill.

Read more night-time hunting insight in our feature on Pen Patrol: Night-time Foxing Tactics.

Related Articles

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

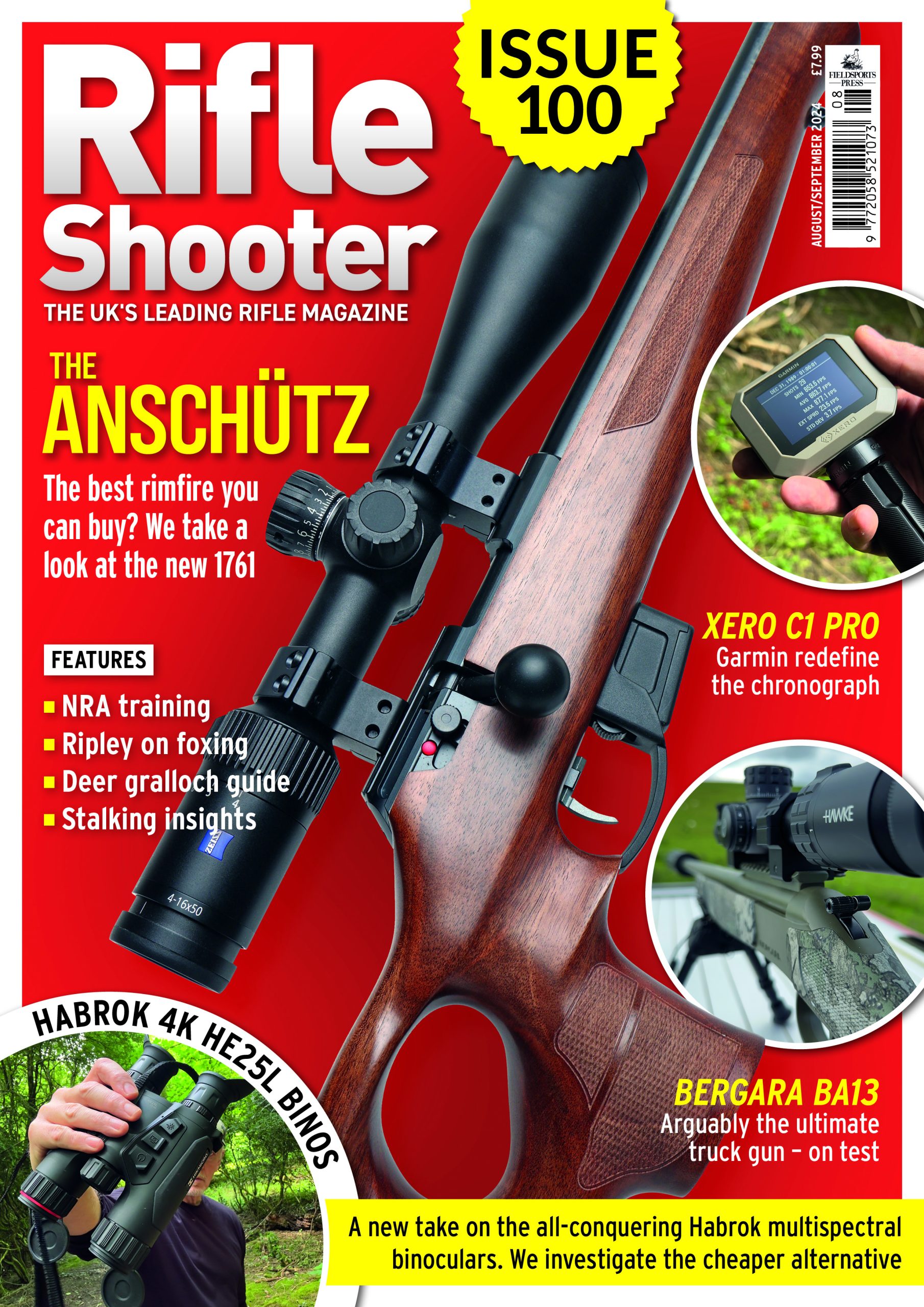

Subscribe to Rifle Shooter

Elevate your shooting experience with a subscription to Rifle Shooter magazine, the UK’s premier publication for dedicated rifle enthusiasts.

Whether you’re a seasoned shot or new to the sport, Rifle Shooter delivers expert insights, in-depth gear reviews and invaluable techniques to enhance your skills. Each bi-monthly issue brings you the latest in deer stalking, foxing, long-range shooting, and international hunting adventures, all crafted by leading experts from Britain and around the world.

By subscribing, you’ll not only save on the retail price but also gain exclusive access to £2 million Public Liability Insurance, covering recreational and professional use of shotguns, rifles, and airguns.

Don’t miss out on the opportunity to join a community of passionate shooters and stay at the forefront of rifle technology and technique.