Adaptive deer management: basing plans around credible targets

Niall Rowantree looks at Scottish deer management & its sometimes exaggerated role in achieving environmental objectives

Deer management decisions are characterised by a level of uncertainty because many responses reflect a range of interacting ecological systems. Faced with this knowledge, while we can use modelling to predict the impact of our management decisions, this would need to be sufficiently robust in quality and context.

The challenge of effective modelling is in the assumptions we make in regard to how habitats and systems will behave in a given period of time. It is crucial that we strive to improve our understanding of what influences habitats and ecosystems – rather than get caught up in an environmental vision that can, at times, be disconnected from reality.

As we move forward, we are developing knowledge on the growth rates of tree seedlings and developing our understanding of what wild habitats should look like. However, this is becoming increasingly complex as we are undoubtedly entering an era where species are declining at their fastest rate ever. Our uncertainty of biological processes makes the prediction of outcomes of any management intervention very challenging.

So how does this affect deer management? Well, for one thing, it would be an awful lot easier for us all if deer would actually read or stick with the plan! In many instances, instead of adapting our vision, we are reacting to an unexpected outcome.

Over-population

I, for one, am the first to admit that in some parts of Scotland there were too many deer and, in some areas, this may still be the case. However, that alone is not the single reason for the changing habitat in Scotland – or for the failure in the delivering of some visions of habitat restoration. This is a crucial part of the discussion as no level of deer management can be expected to deliver on the impossible and if habitats and species are failing to recover for reasons other than deer, continued expense and focus of resources is futile.

In habitat terms, Scotland is not an old country. Not so very long ago, it was covered in ice with sedimentary evidence suggesting ice sheets receded around 14,000 years ago. The development of habitats here are much younger than other parts of the planet, so it is important when planning actions that change land use and influence communities in order to benefit these habitats, that it is not at the expense of other parts of the world.

We live in a consumer society and if we cannot get the things that we need here in the UK, then we are likely to draw them from other parts of the world, which in biodiversity terms could be more valuable and therefore represent a greater loss. So, with this in mind, deer management needs to be based around credible targets in context with credible environmental objectives – that include people’s livelihoods and whole communities.

Post-pandemic

As we emerge from the Covid-19 pandemic and when the influences of Brexit start to influence land management and agriculture, there will be an opportunity to reflect on the credibility of land management objectives. For example, the expansion of forest cover is a credible target, but these forests need to be established in the right places, and on the right soil types where they can effectively secure carbon and provide a viable socio-economic resource to a rural community. Equally important are our peatlands or moorlands, as they are effectively one of our best carbon capture mechanisms and it is with almost shock or disbelief that we are starting to see instances again of deep furrow ploughing on peatland, which defeats the whole idea of carbon capture. Undoubtedly, whichever way we go, deer will play an increasingly influential role in delivering our objectives.

So, it is essential that adaptive management identifies this in the type of habitat selected for forest or wild places. It is disheartening for deer managers who have worked very hard over the last 20 years to deliver a range of public benefits and habitat restoration to be perpetually accused of failing, when often factors out of their control are influencing the desired outcome. In many of the ancient woodland areas in Scotland, climate has played a devastating role in the success or failure of the forest, and non-native species now run rampantly through the forest, regenerating and outperforming the native species.

In these situations, it is misleading to the public to place all the blame on herbivore impacts and we can only surmise that this is to deliver a political statement rather than environmental success. It is important after the last year’s almost forced shutdown of most land management activities by the public sector and NGOs, that as we reboot, we take the opportunity to get around the table and thrash out effective policies that can be delivered – and deer management is an essential pillar in all of this.

Many of us look at the proposals being directed towards agriculture south of the border with a degree of interest as there appears to be the emergence of a suite of opportunities that will allow areas to establish new woodlands and restore ancient ones while leaving a path for agricultural production. Whether Scotland will follow suit remains to be seen.

In my opinion, there will be a desire to cling to something similar to the current EU policies in the hope that if Scotland can rejoin Europe it will be easier for them to align – but I could be proven wrong.

Turbulent times

Fieldsports have gone through a period of doom and gloom of late, with every element from driven shooting to deer stalking suffering from negative pressure, and this was borne out by a recent survey which showed a high percentage of stalkers/gamekeepers having decreased confidence in the long-term viability of their chosen profession. This is very much at odds with the reality of a reforested Britain. Many countries in the world are envious of our cohesive approach, particularly of deer management in Scotland, and far from trailing behind them in competence, the abilities of our country’s deer stalkers are to be applauded.

I would urge everyone involved in the management of deer, at any scale, to ensure that they have a deer management plan in place that reflects as much of their deer range as possible and draws in all those who have an interest in deer in the local community. The range of desired habitats for that area plays a key role in target setting and ensuring that all targets are credible. It is entirely realistic that the targets include socio-economics and food production alongside healthy habitats that secure carbon, be it heathland or forest.

As we move forward, we will increasingly hear about the climate emergency and we should expect greater scrutiny of land management activities at every level. We can already see this developing north of the border with licensing on the cards or in motion for a lot of land management activities in the uplands, and I believe that this is the shape of things to come. As a result, this underlines the need to have robust management systems in place to be able to demonstrate adaptive, effective deer management plans.

Related Articles

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

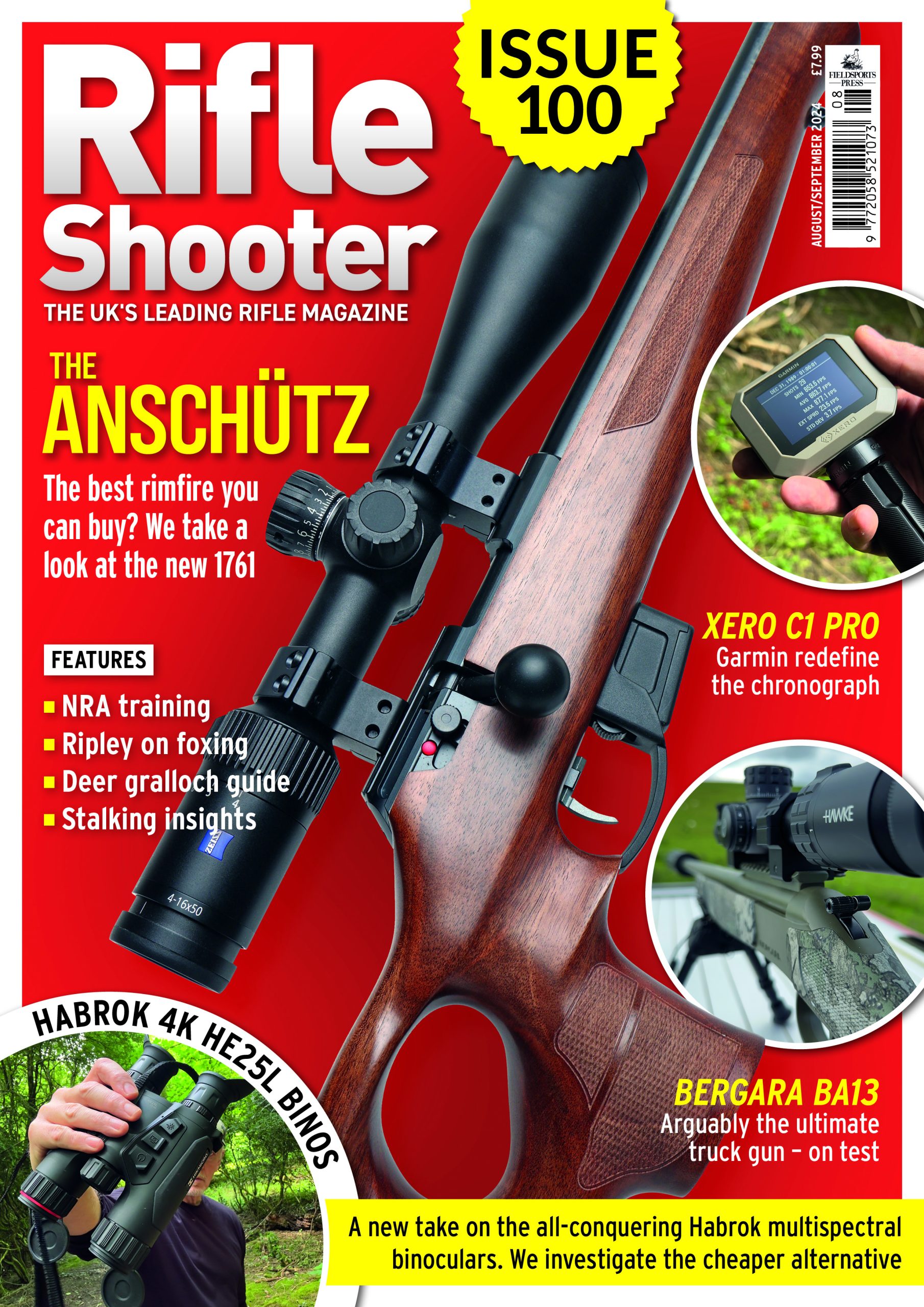

Subscribe to Rifle Shooter

Elevate your shooting experience with a subscription to Rifle Shooter magazine, the UK’s premier publication for dedicated rifle enthusiasts.

Whether you’re a seasoned shot or new to the sport, Rifle Shooter delivers expert insights, in-depth gear reviews and invaluable techniques to enhance your skills. Each bi-monthly issue brings you the latest in deer stalking, foxing, long-range shooting, and international hunting adventures, all crafted by leading experts from Britain and around the world.

By subscribing, you’ll not only save on the retail price but also gain exclusive access to £2 million Public Liability Insurance, covering recreational and professional use of shotguns, rifles, and airguns.

Don’t miss out on the opportunity to join a community of passionate shooters and stay at the forefront of rifle technology and technique.