Conservation Controversy

Emily Damment delves into the complex subject of trophy hunting after Botswana offers to educate Europe on the reality of human-wildlife conflict

Everyone who has worked in agriculture, wildlife management or environmental stewardship will be familiar with outside interference from the desk- bound and uninformed. Recently the president of Botswana – Mokgweetsi Masisi – produced the best response on record to this kind of meddling from Germany’s environment ministry.

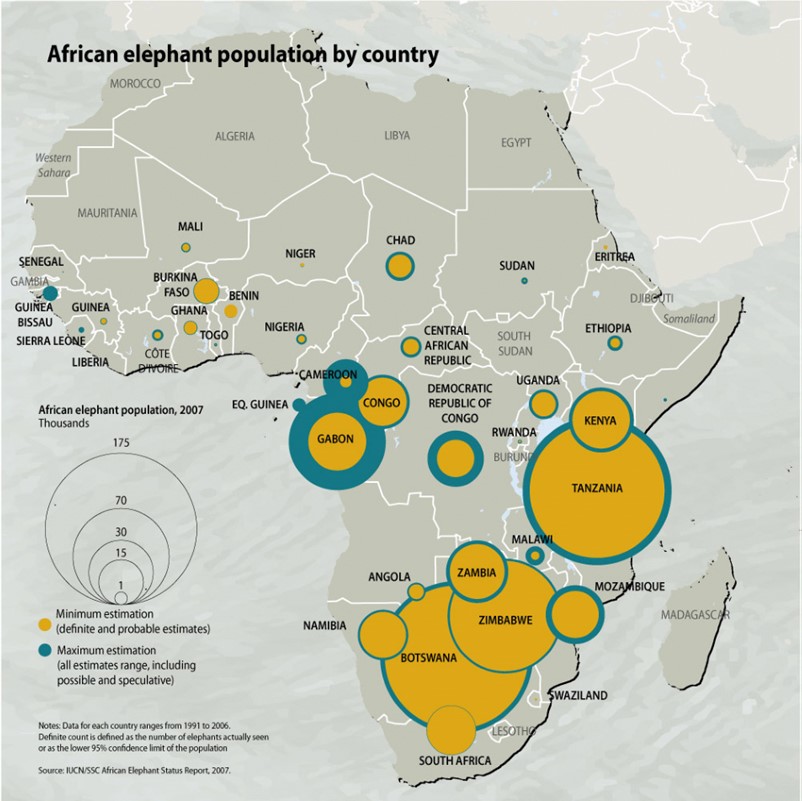

Led by the Green Party’s Steffi Lemke, the ministry raised the possibility of imposing stricter limits on the import of hunting trophies amid concerns over wildlife populations in African countries. Botswana is home to the world’s largest elephant population and Germany is one of the leading EU importers of elephant trophies. An import ban would inevitably affect elephant hunting in Botswana.

Masisi’s response was to offer to send 20,000 elephants to Germany to help people understand the human-wildlife conflict. Speaking to The Guardian, he said he believed that many Europeans perceive the value of elephants as superior to human life in Botswana. He accused the German government of sitting comfortably in Berlin while people in Botswana paid the price of preserving these animals for the world.

Germany is not the only country under fire from Masisi for such policies. In March the UK received its own offer of 10,000 elephants – it was suggested that they could perhaps roam freely around London’s Hyde Park. You would have to go back several hundred years in Britain to witness the type of human-wildlife conflict that Masisi refers to. It’s one of the reasons we no longer have wild bears or wolves in this country.

UK VIRTUE SIGNALLING

The UK Hunting Trophies (Import Prohibition) Bill ground to a halt in the House of Lords in September 2023, after the 60 amendments tabled by those opposed to its passing proved too time-consuming to debate fully. Earlier this year the whole process began again, and in March the bill passed through its second reading in the commons, prompting Masisi’s offer.

Presented as legislation that will prevent the further decline of endangered species, the discussion surrounding this piece of legislation has been laden with emotion from the start.

Trophy hunting has been branded “appalling”, “cruel” and the pastime of a “tiny and mindless” minority that generates “next to no revenue for wildlife conservation”. It’s not surprising that the Bill has garnered strong support from the public, but during its initial reading in 2023 it was announced that it also had the backing of African leaders and communities.

A joint letter addressed to the Minister of State in the Foreign Office from high commissioners of Namibia, South Africa, Tanzania and Zimbabwe threw that last point into question. It argued that well-managed trophy hunting contributes to reductions in habitat loss and poaching, and has proved a demonstrable conservation tool for multiple species, including endangered black rhinos.

This year, along with the Botswana president’s clear opposition to the Bill, there has also been a letter from the Namibian Environment Minister denouncing the Bill as a “regressive step towards neo-colonialism” that implies that the UK’s insight and expertise supersede those of the countries in question.

Perhaps most impactfully, further damning correspondence was received from Maxi Louis – the director of the Namibian Association of Community-Based Natural Resource Management Support Organisations (NACSO).

NACSO assists conservancies and other rural organisations in the management of their natural resources for their own benefit, and in the enhancement of conservation through community-based resource management activities.

For example, aggregations of private farms are formed, where landowners come together to include conservation management in their land-use planning. Much of the focus is on wildlife, with trophy hunting representing an important income stream. Louis’s letter ends by stating that wildlife in Africa is flourishing “because of our management”, and asks for no more “arrogant, ignorant virtue signalling”.

She might have hit the nail on the head here. According to Sir Bill Wiggin, who participated in the Commons debate, the UK has imported just 72 CITES-listed species as hunting trophies over the last 22 years, whereas over the same period the pet industry has traded in over 560 listed species.

It does make one wonder why, if the goal is to protect these species, there is such focus on trophy hunting when even opponents to the sport concede that it has generated conservation benefits in some cases.

The biggest problem with the Bill for those opposed to it has always been the absence of any plans to replace the lost revenue when African hunting tourism consequently declines. That revenue allows hunting to be competitive with other potential land uses which, unlike hunting, do not value or seek to preserve wildlife populations.

CONFLICT REDUCTION

When trophy hunting is well managed it creates incentives for communities living close to dangerous wildlife to preserve healthy populations and habitats. Locals can find employment with the hunting outfitters; tourism in the area increases, creating jobs and income; anti-poaching rangers are employed to protect wildlife in the hunting reserves as well as in the national parks that the reserves often surround; villagers relying mainly on subsistence farming are provided with meat from regulated hunting, reducing the unlicensed poaching of bushmeat; and in many cases infrastructure improvements are made, such as the provision of running water and toilets.

The key point of all this is that trophy hunting reduces human-wildlife conflict. The community is provided with tangible rewards for living alongside large, dangerous animals that can and do destroy property, raid crops, take livestock and kill people. Elephants in particular are destructive and dangerous and can wipe out a farmer’s entire livelihood in just a few hours.

A highly regarded example of trophy hunting incentives that have successfully reduced human-wildlife conflict is the Communal Areas Management Programme for Indigenous Resources (CAMPFIRE) in Zimbabwe. Established in 1989, it encourages rural communities living on communal lands to conserve wildlife. Much of the communal land in Zimbabwe is characterised by low rainfall and poor soils, making life difficult for its inhabitants, many of whom rely on subsistence farming to survive. Unsurprisingly, human-wildlife conflict driven by crop and property destruction is a huge issue.

The CAMPFIRE program depends heavily on hunting tourism to generate economic benefits to supplement the communities’ subsistence farming, and the income from elephant hunting has given local inhabitants a reason to value the animals, rather than viewing them as a destructive, dangerous threat to their existence. It is estimated that households participating in CAMPFIRE saw a 15-25% raise in their incomes, while funding was also provided for infrastructure development projects providing schools, clinics and water services.

Trophy hunting import bans in other countries have in the past badly affected the program and its benefits for local populations. The village of Mahenye used community dividends from the CAMPFIRE program, generated through elephant hunting, to pay for school buildings, a lorry, a tractor and two electric corn-grinding mills. The short-lived US elephant trophy import ban, introduced in 2014, caused a huge slump in revenue and the Mahenye CAMPFIRE Project had to make six of the 15 workers it had employed redundant, leaving the elephants vulnerable to poaching and the community without investment.

WILDLIFE DECLINE?

It’s a common misconception that legal, well-managed trophy hunting is contributing to the decline of Africa’s iconic wildlife. It is not. Taking southern white rhinos as an example, since

trophy hunting was legalised in Namibia and South Africa in 1968 the population increased from around 1,800 to 18,000 by 2018. Highly regulated permits for black rhino hunts were introduced in 2004 and again the population increased from 3,500 to 5,500 by 2018.

Rhino hunting aims to remove older, dominant, non- reproductive males from groups to make way for younger males of reproductive age, which bolsters the population. Unlike poaching, which is reduced in hunting reserves that can pay for anti-poaching rangers, individual animals are carefully selected and the females are generally preserved.

The greatest threat to wildlife – not just in Africa but globally – is habitat loss and destruction. As human populations grow, more habitat gives way to infrastructure, food/energy production and housing. The closer humans live to wildlife, the more they are brought into conflict with it, and the more incentives are required to tolerate it. This is the benefit of trophy hunting that is not talked about enough. It seems many are unable to get past the emotive subject of killing an animal – especially those in charge of legislation in this country.

The animals this Bill concerns evoke strong emotions that have found their way into what should be a purely evidence- based discussion. Elephants, lions and rhinos are indeed majestic and exotic – they are ‘bucket list’ animals for hunting creates huge resources across Africa and is a key factor in anti- pouching efforts many Western wildlife enthusiasts. Perhaps this is why, in European debates on policies relating to their management, there seems to be little consideration for the communities that are struggling to live alongside them.

The UK Bill has highlighted above all else the complex relationship between hunting and conservation, and the desperate need for evidence-based discussions to be at the heart of any related legislation. This is especially true when the impacts will not be felt by those enforcing it but by often impoverished communities in countries far away.

When we consider the CAMPFIRE project, NACSO, the successful conservation of black and white rhinos, and Botswana’s booming elephant population, it’s clear that when conducted ethically and in partnership with local communities, trophy hunting can help to conserve healthy wildlife populations and habitats. Given that this is the stated aim of the Bill, we can only hope that these examples are given further consideration as it continues its passage through parliament.

Related Articles

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

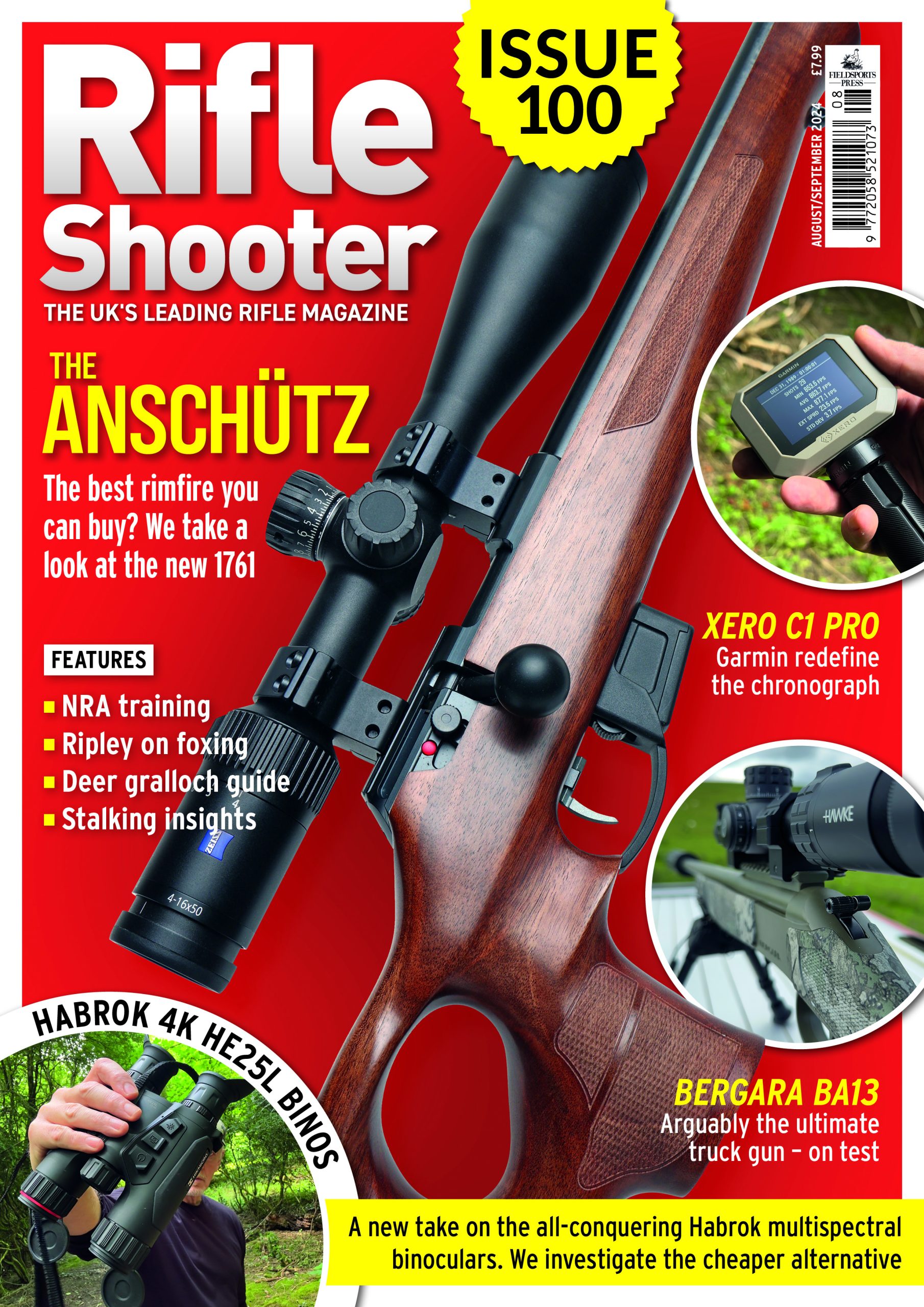

Subscribe to Rifle Shooter

Elevate your shooting experience with a subscription to Rifle Shooter magazine, the UK’s premier publication for dedicated rifle enthusiasts.

Whether you’re a seasoned shot or new to the sport, Rifle Shooter delivers expert insights, in-depth gear reviews and invaluable techniques to enhance your skills. Each bi-monthly issue brings you the latest in deer stalking, foxing, long-range shooting, and international hunting adventures, all crafted by leading experts from Britain and around the world.

By subscribing, you’ll not only save on the retail price but also gain exclusive access to £2 million Public Liability Insurance, covering recreational and professional use of shotguns, rifles, and airguns.

Don’t miss out on the opportunity to join a community of passionate shooters and stay at the forefront of rifle technology and technique.