Deer management for trophy hunting with Mike Allison – Jelen Deer Services

A detailed guide on every aspect of deer management for trophy hunting; with specific information on sika, fallow, red, roe, muntjac, and Chinese water deer credit: Archant There are few of us that will be fortunate enough to be an employee on an estate solely responsible for managing the deer, whether park or wild, on

Would you like to appear on our site? We offer sponsored articles and advertising to put you in front of our readers. Find out more.

A detailed guide on every aspect of deer management for trophy hunting; with specific information on sika, fallow, red, roe, muntjac, and Chinese water deer

There are few of us that will be fortunate enough to be an employee on an estate solely responsible for managing the deer, whether park or wild, on behalf of the landowner or employer. The alternative option is to run a commercial enterprise as a tenant or lessee, where the deer management decisions are down to you and your income is derived from selling stalking, as opposed to an employee receiving a salary for running an enterprise.

It is believed by many that commercial stalking and deer management are two different things. In fact, commercial stalking on many estates is an integral part of the overall management, and not least an important economic element providing a vital income, from ground which may otherwise yield little revenue.

Although it may well be an integral element of the wider estate management strategy, the aims of commercial stalking may well conflict with other aspects of management, such as forestry and agricultural crop protection, especially if a properly structured plan is not in place at the outset.

Many people, even some of those involved in deer stalking and management, may find the idea of stalking and killing a deer for its antlers to be abhorrent. However, it must be remembered that the sale of trophies can form a significant element in effective, sustainable and profitable deer management.

This article deals with the differences in management approach, and discusses ways in which we can ensure that a commercial (trophy) stalking enterprise can coexist, without detriment to one objective or the other.

Trophies

Trophy deer are usually seen as heads that are of better quality than just culls. They are usually animals that are a good representation of the typical antler form of the deer species concerned. Obviously, when the animal exceeds the quality of a mere representative head and becomes a ‘trophy’, then the value goes up proportionally.

So why does this make them more ‘valuable’? Well, it is (or should be) relative to the length of time the animal has spent on the ground, eating crops, damaging crops, being observed, assessed and protected for sometimes many years by a deer manager, who is being paid by an estate owner or, alternatively, has to make a living for himself.

The value of such animals should be relative to the quality of the trophy, and to the five, six or seven years of management that has been invested in that animal. However, it is also relative to the genetic superiority of the animal – a result of good management based on the removal of poorer animals from the breeding population, and on the prevention of sub-standard animals from metapopulations establishing themselves in the resident population.

In contrast, many estates have benefited from the trophy quality produced on neighbouring estates and farms, simply through the effects of population dynamics – especially in roe deer, where older, higher-quality bucks have been displaced by younger, stronger animals. In other words, estates may lose out through their own shortfalls in management, or poor management.

Trophy stalking

Each year, most estates will yield male animals that are able to be sold to sporting clients, or trophy hunters. Prices for trophy animals range from only £75 per head for a cull roe buck, up to many thousands of pounds for a top-class trophy red deer.

The very fact that exceptional male deer are worth a lot of money can be to the detriment of the species, locally and regionally, from a quality viewpoint – especially where short-term leases are involved. In some cases, where there are no guarantees that managers will have the stalking in the next lease period, the temptation to ‘harvest’ good-quality animals before leaving is very strong indeed.

The general outlook is: why should someone else benefit from the ‘manager’s’ hard work in the previous management period? In recent years, this thought process has led to the destruction of many fine animals, invariably ones that would have been much better left to breed or grow on a few more years. This may well be the case with the males of almost all the six species, particularly the territorial and semi-solitary roe.

The systematic harvest of trophy animals should be a sustainable, year-on-year process, but where other estate enterprises are paramount – such as the protection of agricultural and forestry interests – then the production of trophies combined with effective damage control can be problematic, as both management strategies are somewhat incompatible.

As part of the deer manager’s approach, this is one of the issues that should form part of the initial plan, in line with the owner’s objectives.

The Key Features

To produce trophy roe bucks

As discussed earlier in this series, management plans need to remain flexible to allow for direct, or indirect, influences that may affect the management strategy employed. In general, however, a trophy production strategy can be loosely based on the following:

? Does – Culling mature, breeding-aged does, should be avoided, unless done for a welfare reason. Mature does will be hefted to a particular area, and research carried out at Eskdalemuir in the Borders region suggests that mature females will rarely move out of a small area throughout their entire lives, and if they do then they will normally return within a short time.

? Yearling does – These will undoubtedly be forced to move from the home range of the mature doe, and if not culled they may be lost to the estate as they emigrate to other areas.

? Yearling bucks – Cull all yearling bucks that do not form six points, or at least a good four strong points, in their first head. By ‘good’ we are mainly referring to antler length above the ears, when the ears are in the normal alert position. This is especially true in the south of England where, generally speaking, given the suitable habitats, if a buck cannot produce a respectable first head then, genetically, it probably doesn’t possess the capability to produce a top-class trophy.

? Mature bucks – Generally mature bucks will be highly territorial, often following the same movement patterns each day until an event, or series of events, may cause them to change the pattern. This in itself can work against the deer, as mature quality bucks become ‘easy targets’, especially during the rut where deer movements and locations can be very predictable.

Territorial animals and tree protection

As with people, older age tends to bring with it routine, and this is true with older bucks. The routine may change when younger bucks begin to encroach on the mature buck’s territory. When the pressure of younger bucks becomes too much, then mature bucks may become stressed, and eventually move from the area altogether. This may cause the emigration of quality animals onto neighbouring land, leaving several ‘troublesome’ bucks in their place, which could cause increased tree damage as each competes for a smaller ‘territory’ of their own. More importantly, from an economic viewpoint, neighbouring estates will reap the benefits of your hard work over the past five years or so.

This can be avoided by paying attention to what animals are in and around the mature buck’s territory, and if the presence of the underlings is not ultimately of benefit to the management aims, then they should be removed as early in the season as possible, otherwise they may cause quality bucks to move away.

By keeping the territorial bucks in place, and tolerating one or two upcoming animals, we can effectively ensure tree protection to an extent. Large territorial bucks (and does) will effectively keep other animals away, so there is some benefit to keeping them in areas that may be vulnerable.

However, when such bucks are removed – and especially if there are no upcoming bucks to take their place – then damage levels, especially fraying damage, can increase up to four-fold, as several younger animals may compete for a portion of the same territory.

Trophy red stags

For many, the red deer is the largest and arguably one of the most iconic species of deer, representing the pinnacle of physical sporting challenges throughout most of Europe. There are some animals of outstanding quality throughout the UK, and especially in Europe.

In the UK, it would be a challenge to beat the quality of red deer found in Norfolk and Suffolk, and in parts of the West Country. This is due mainly to the quality of the lowland environment they live in. In mainland Europe, Bulgaria, Hungary and parts of the Carpathian mountain range support some of the finest quality red deer in existence – often with the highest price tags!

Red deer stalking as we know it today began in the Highlands of Scotland, in particular the Balmoral and Athol estates, where Queen Victoria and Prince Albert were the catalysts of the sport; very soon after, it became fashionable amongst the gentry.

The fact that many stately homes throughout most of the UK and Europe have at least one red deer trophy on the wall is indicative of their past and present attraction as a sporting animal, especially amongst the more affluent.

Due to the increase in the numbers and range of red deer nationally, the recognition of red stags as a lucrative sporting business opportunity, and the relative increase in disposable incomes since the Victorian era, quality red deer stalking is now accessible to most willing sportsmen and sportswomen.

The attraction of a large set of antlers has, however, led to the destruction of quality among many wild herds in the UK. The New Forest areas are a notable example. Red deer are still there in abundance in some locations, but antler quality has deteriorated throughout the past three decades.

Through careful and disciplined management, red deer can provide a lucrative and sustainable source of income, but the quest for sporting value must not overlook the potential of the species to cause widespread damage, especially where red deer exist in large numbers.

Trophy fallow bucks

With good management, fallow bucks are well capable of producing outstanding trophies, but the demand for quality fallow trophies is somewhat limited in the UK, especially as many places in Europe and throughout the world – from New Zealand to USA to the Emirates – hold fallow deer, and so the demand from overseas clients is limited.

It is questionable as to whether there is really a viable incentive to manage fallow for trophies. Given their transient nature, unless the deer manager has control over their entire range, (potentially 10,000 acres plus) then the chances of being able to either affect specific management, or gain the benefits of long-term management, are somewhat unreliable.

Considering the extensive damage that fallow are capable of inflicting on farm and forest crops, balanced against the likely returns for trophy animals, there is probably little point in developing a management plan to produce trophy fallow bucks. Although if a trophy animal does present itself while the client is shooting roe, sika or reds, then the chances are that he/she will take the opportunity.

Trophy sika stags

In contrast to fallow, the demand for quality sika stags is now unprecedented, especially for medal heads, and is increasing year on year. Sika trophies are sought after by visiting sportsmen/women, more now than ever before, and the demand is reflected in the prices charged and regularly obtained.

As a sporting animal, sika stags are probably one of the most challenging. Their autumn colour alone allows them to blend into most woodland backgrounds; combine this with the fact that they are often in the presence of a group of several observant hinds, and it is no wonder that stalkers often overlook these while transfixed on their ‘stag of a lifetime’. Therein lies the challenge and excitement of sika stalking.

As a species, sika are renowned for being a ‘tough’ animal. Every year, many ‘well-shot’ animals make their way into cover, and are never recovered. In many cases, the absence of blood trails and strike debris can lead shooters to assume a miss.

It must be remembered that of all the wild species in the UK, sika deer in good condition tend to carry the most subcutaneous fat. It is very likely that fat deposits can block entry and exit holes, preventing not only blood flow out of the animal, but also maintaining some respiratory function, as air loss through the bullet holes is generally restricted.

Trophy muntjac bucks

The fact that, outside of their native Asia, muntjac are only present in the UK makes them a very sought-after species, and good-quality trophies are relatively easy to produce on good-quality ground, coupled with good management. However, muntjac are an invasive species, and there needs to be a careful balance between maintaining higher populations for trophy stalking, and the management of biodiversity.

Numbers can soon spiral out of control causing damage to flora, as well as disruption of pheasant drives, and can often cause the management of muntjac for trophies to be sacrificed in favour of woodland protection. As so often happens, the presence of high-value deer can lead some ‘managers’ to promote population increase.

One of the challenges of muntjac stalking is their small size, and once ground cover exceeds 30cm in height, a muntjac can move – and breed! – very easily without being observed at ground level. Being known as a species that are often on the move only serves to compound the difficulty in stalking them effectively. One of the most effective means of shooting muntjac is from well-positioned high seats.

Trophy Chinese Water Deer

While representing one of the most sought-after species in the UK, not least due to the scarcity of the species nationally, Chinese water deer nevertheless provide one of the least sporting challenges. In the fields of parts of Bedfordshire and Cambridgeshire it is not uncommon to observe groups of five to 10 animals and – compared to other deer species – they are relatively easy to approach and shoot.

For many, the attraction is the fact that they are the least distributed species throughout the UK and, similarly to muntjac, they carry visible tusks. These can be several centimetres long in the males.

Because of their relative scarcity in the UK, they command generally higher prices than one would expect from what is, essentially, one of the least interesting sporting animals on the deer stalker’s quarry list.

In many cases, the greatest attraction among UK stalkers is in ‘collecting’ trophies, to make up the last of the six UK species. The person who can offer stalking of all six species in the UK is not only in a fortunate position as a deer stalker/manager, but holds the availability of one of the most sought-after (and therefore the most saleable) options available to both UK and overseas sportsmen and sportswomen.

Related articles

AN ICELANDIC SAGA

A detailed guide on every aspect of deer management for trophy hunting; with specific information on sika, fallow, red, roe, muntjac, and Chinese water deer credit: Archant There are few of us that wi...

By Time Well Spent

AFFORDABLE INNOVATION

A detailed guide on every aspect of deer management for trophy hunting; with specific information on sika, fallow, red, roe, muntjac, and Chinese water deer credit: Archant There are few of us that wi...

By Time Well Spent

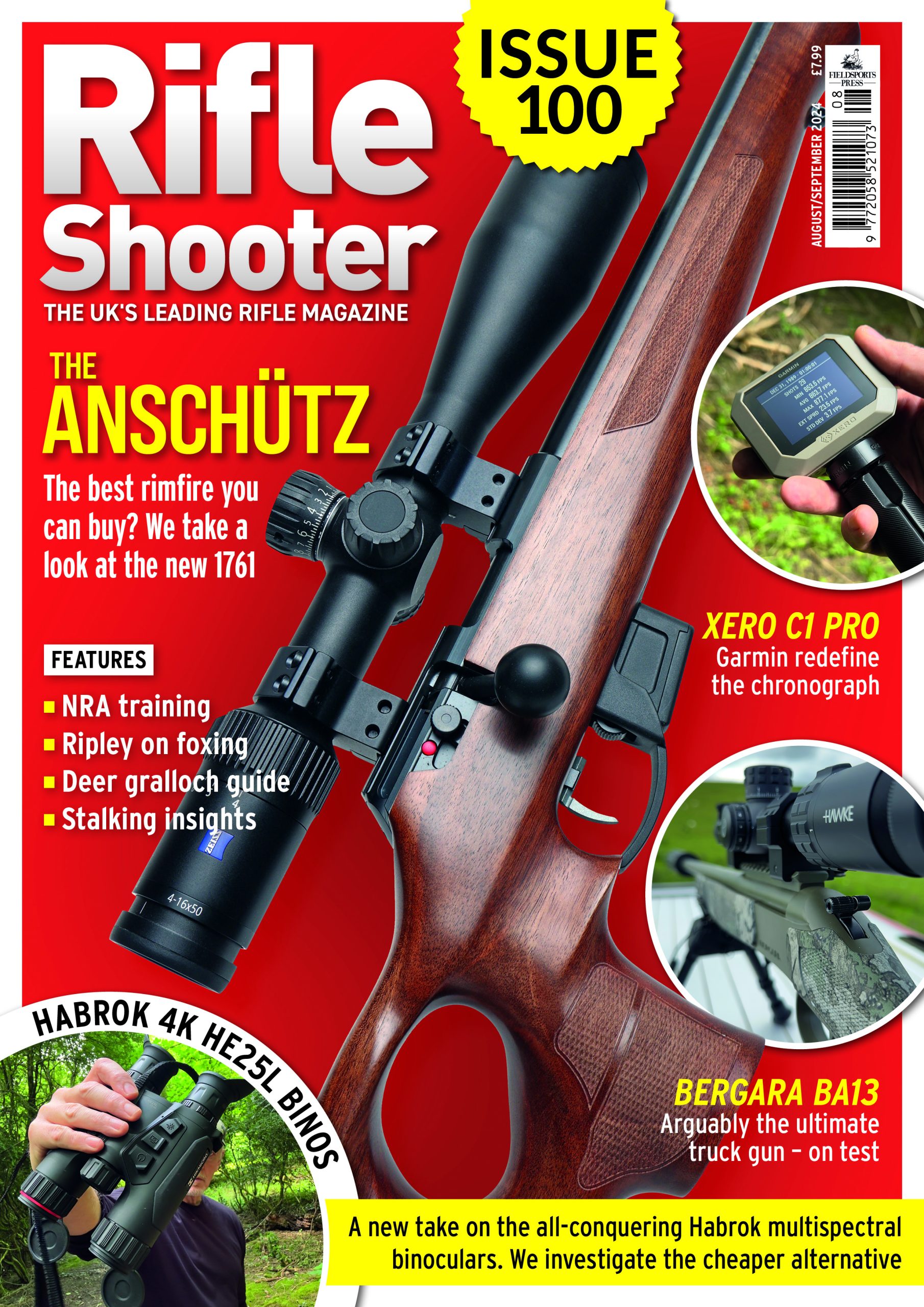

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

Subscribe to Rifle Shooter

Elevate your shooting experience with a subscription to Rifle Shooter magazine, the UK’s premier publication for dedicated rifle enthusiasts.

Whether you’re a seasoned shot or new to the sport, Rifle Shooter delivers expert insights, in-depth gear reviews and invaluable techniques to enhance your skills. Each bi-monthly issue brings you the latest in deer stalking, foxing, long-range shooting, and international hunting adventures, all crafted by leading experts from Britain and around the world.

By subscribing, you’ll not only save on the retail price but also gain exclusive access to £2 million Public Liability Insurance, covering recreational and professional use of shotguns, rifles, and airguns.

Don’t miss out on the opportunity to join a community of passionate shooters and stay at the forefront of rifle technology and technique.