DEER TRACKING DOGS

As the use of deer-tracking dogs grows in the UK, discussions arise about breeds and standards. Rudi van Kets explains how European models could guide development

Until about 15 years ago, the thought of using a tracking dog for deer, let alone having an organisation concerned with such things, was unthinkable in the UK. A possible reason for this was the strict import rules for dogs, which at that time required them to be quarantined for four months.

Today, the situation is different, and it seems that growing numbers of people are engaging in this practice. A quick browse of shooting forums reveals all sorts of intense and, at times, out-of-control conversations arising on the subject of deer tracking. Many of these discussions, however, tend to peter out into nothing after a while.

Meanwhile, various groups or associations are being formed, each devising its own philosophy or strategy based on what they consider to be ‘common sense.’

How do we unify and strengthen all these efforts? It may be desirable to look at countries that have been working on this for some time and examine the development of dog breeds and training structures they have adopted.

An important organisation in this regard is the Fédération Cynologique Internationale (FCI). This overarching organisation already represents the main deer-dog breeds and has established a breed standard for each one. To better understand their work and the countries involved, it’s worth checking online to see which nations are members of this organisation.

Unfortunately, the UK is not one of the countries affiliated with the Fédération Cynologique Internationale (FCI). The member countries each have their own national organisation to defend the interests of their affiliated clubs. In my native Belgium, for example, this role is fulfilled by the KKUSH. Membership in this organisation ensures, among other things, that members face fewer issues with officials, as they can demonstrate adherence to a set of rules and breeding standards. It’s a good example of self-regulation in action.

No country in Europe has more associations than Germany. Much of the development in dog breeding and training has emanated from Germany, and many people look to it for guidance. In Germany, every pedigree group is affiliated with Das Jagdgebrauchshundewesen, and each has its own specific tests, including those focused on tracking work.

There are both supporters and opponents of using certain traditional breeds for tracking, such as the Labrador or Springer Spaniel. These breeds are not officially recognised as deer-tracking dogs by the FCI. However, in Germany, Das Jagdgebrauchshundewesen provides these breeds with the opportunity to undergo testing. This allows them to prove their worth in tracking, even without official recognition.

Another issue relates to non-compliance with prescribed rules. For example, one man who failed to pass a theory exam was blocked from owning a purebred Bavarian Mountain Hound. Determined, he obtained another dog of the same breed, but this dog lacked a pedigree and had not undergone any official tests. The man trained the dog independently and now works between 200 and 250 trails a year.

Last year, I joined this man and his Bavarian Mountain Hound to track wild boar. The dog performed perfectly, following the trail for 5 km before concluding it. That kind of experience cannot be faked. However, because of his lack of formal credentials, this hunter remains excluded from many clubs, leaving him a solitary figure in the tracking community. Is that fair? Opinions differ, with some supporting his exclusion and others opposing it. For now, he remains outside the elite circles that represent hunters.

Deer Stalking Fair

In 2019, I attended the Deer Stalking Fair in Scotland with two members of our Belgian association. We were guests at a stand that, like us, focuses on tracking work. During the event, we gave a presentation covering how tracking work is organised on the Continent within the FCI structure, the associations involved at a national level, their various partners, and other related topics.

At the end of our talk, we were asked numerous questions. The most common was why such systems and organisations exist on the Continent but not in the UK. Other questions focused on how long it takes to establish an association, how to gain wider recognition, and how to organise tests.

Preserving the international standards of dog breeds was another challenging topic. Some people feel pressured to accept more breeds, often for financial reasons. However, I believe this would be a mistake. Since tracking work arrived in the UK, the subject has sparked heated debates. Among the most contentious issues is which breed should serve as the industry standard—the Hanoverian Scent Hound or the Bavarian Mountain Hound. Many misunderstandings have arisen from these discussions.

Other Breeds

Using other breeds for tracking is certainly possible. On the Continent, tracking tests exist for various dog groups, including pointers, setters, retrievers, flushing dogs, and water dogs. However, these tests have not been widely adopted. The purpose of such tests is to evaluate whether dogs from these groups can follow a track of a minimum distance within a maximum timeframe. Retrievers and Springer Spaniels, for instance, are rarely or never used on the Continent for tracking.

Inevitably, everyone who works with dogs believes their breed is best suited for their chosen hunting discipline. Participants in these debates often defend their opinions passionately, as emotional attachment to one’s dog is strong. Many of us have likely taken part in a discussion about dog suitability that escalated into a heated argument.

We need to step back from such debates. I believe it’s wise to consult existing rules and seek advice from breed clubs, which possess extensive knowledge and expertise. These organisations have accumulated a wealth of information over many years and are often happy to share it.

There will always be those who support or oppose specific breeds and types of dogs. My hope is that we avoid doubting each other’s intentions or expertise when making our own informed choices.

Related Articles

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

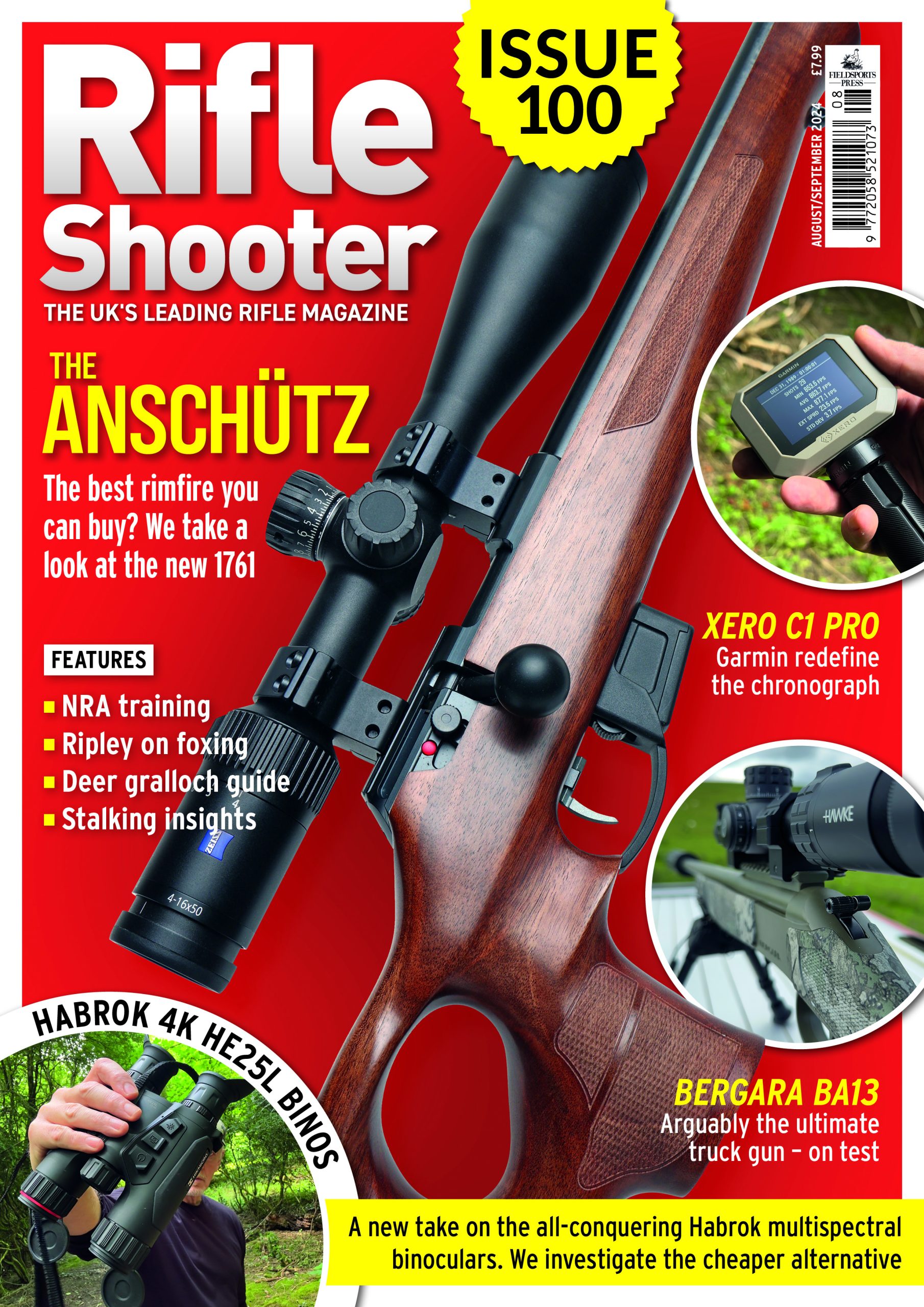

Subscribe to Rifle Shooter

Elevate your shooting experience with a subscription to Rifle Shooter magazine, the UK’s premier publication for dedicated rifle enthusiasts.

Whether you’re a seasoned shot or new to the sport, Rifle Shooter delivers expert insights, in-depth gear reviews and invaluable techniques to enhance your skills. Each bi-monthly issue brings you the latest in deer stalking, foxing, long-range shooting, and international hunting adventures, all crafted by leading experts from Britain and around the world.

By subscribing, you’ll not only save on the retail price but also gain exclusive access to £2 million Public Liability Insurance, covering recreational and professional use of shotguns, rifles, and airguns.

Don’t miss out on the opportunity to join a community of passionate shooters and stay at the forefront of rifle technology and technique.