Long distance target shooting – wind effects and ballistics

Andrew Venables from WMS Firearms Training looks at long distance target shooting, the effects of wind on bullet paths, and ballistic solutions

Repetition can be very useful when teaching and transferring information, so with no risk of censure, I repeat: there is no such thing as long-distance hunting. The purpose of hunting is to bring home food for the family with certainty; it is not to see if you can hit something a long way away. Shooting at targets (inanimate objects) is a valid form of practice to find one’s limits. As this is a form of play and learning, like wolf cubs stalking each other, it is recreational and without bad consequences, unlike not bringing home food because you missed, or because you have wounded and lost your quarry.

Having established that this is not about using animals as targets, how can we go about increasing our knowledge and confidence in our rifle by recreationally shooting at targets at far longer distances than we will hunt at? The marketplace seems full of solutions, offering sometimes far-fetched promises of hits at 1,000m, or the magic mile shot. In truth, consistently hitting relevant-sized targets at distances over 200m becomes increasingly difficult, since the elements interfere with our best-laid plans. So, how can we shift the balance in our favour?

We have looked at Point Blank Zero (PBR), and at reticles which help us out to 300m plus by formalising aim off, or ‘swaging it’, as I have heard it described. Now we need to understand the principles of measuring the main factors affecting our shot, and applying more precise solutions to ensure finer accuracy. The established best way is by dialling up and left or right from our original zero to counter the effects of gravity, wind deflection and other issues.

Telescopic sights (scopes) which allow us to do this are generically known as ‘target’ or ‘tactical scopes’. They have exposed dials for up/down and right/left, a position for zero, and then units to allow precise elevation and windage adjustments. Often, these are now metric, in clicks of one centimetre at 100m, which also equals three centimetres at 300m, nine centimetres at 900m, and so on…

The other most common unit is the minute of angle, or MOA, with turrets usually marked as one click equalling ¼ MOA at 100 yards, thus utilising imperial and fractional measurements, rather than decimal. Further variations on the theme can offer 0.5cm clicks at 100m, or MOA clicks at 100 yards. I have also seen 0.25cm at 100m clicks, and I must state that I never have, nor ever will, need adjustments as fine as these for my rifle shooting, whatever the range or target; ditto that ¼ MOA click.

Take careful note of which way the turrets turn to achieve up and right. In my youth, all open sights adjusted clockwise for up and right, which seemed eminently sensible. We now have a fairly even split of scopes which offer either up and right clockwise, or up and right anti-clockwise. This can cause all sorts of confusion in the heat of the moment, and I strongly suggest that you standardise one way or the other if you have a few rifles (at WMS we have to use both and it drives me nuts!).

The one-centimetre click system, common to most European made scopes, also equates to the military milliradian and mil dot system, now adopted worldwide. The mil dots I described in last month’s article are standardised as a reflection of 10cm at 100m, 30cm at 300m and 100cm at 1,000m. A tenth of a mil dot is known as a milliradian, which is 1cm at 100m, thus effectively the same as the one-centimetre click on most European scopes.

So, let us assume that you have a laser rangefinder and a target-type scope with exposed turrets, which is set to zero at 100m. It has one-centimetre clicks and we have a target 300m away. What next? Assuming the wind is zero, you need to adjust the elevation turret upwards, but by how much? This will primarily depend on the velocity and ballistic coefficient (BC) of the bullet you are firing. Gravity effects all falling objects in the same manner and at the same rate, so the moment your bullet leaves the barrel it is being dragged down; how long it takes to get to your target will reflect the amount of drop. Its initial velocity, and how well it maintains speed, will decide how long it is in flight; so nothing ‘shoots flat to 300m’, despite what the armchair expert said last night on Facebook.

The following data relates to a 150gr .308 bullet with a muzzle velocity of 2,800fps and a BC of .346; in the middle of deer calibre performance.

There are many ways to acquire the information needed to account for bullet drop. Some ammunition manufacturers helpfully put it on the box, usually with a zero range at 100m/y, and the relevant drop at 200m/y and 300m/y.

If the box says that from a 100m zero your bullet will drop 46cm, then divide 46 by three, which equals 15 clicks (or milliradians) up required. Click up 15, aim squeeze and hit.

If you are in MOA, the bullet would have been 18” low, so at 325 yards (300m) one MOA equals three and a quarter inches. Divide 18 by three and a quarter to make five and a half, or five and a half minutes. If the scope is in ¼ MOA, you need to come up 22 clicks to give the five and a half MOA up required. Click up 22, aim squeeze and hit.

I personally prefer the metric system because decimals were always music to my fraction-addled brain. This system of dialling for range is much more precise than aiming off. Additionally, if it does not go perfectly, you have a solid centre aim point, which you can add a bit of aim-off to for a quick save-the-day follow-up shot. This is preferable to trying to add a bit to a vague aim point which started half an animal high. If your eyes are glazing over and your head is hurting, take a break and then read this twice. I have to do this when I read modern instruction manuals and it helps.

Beyond 300m we enter a scary world of wind meters (anemometers), ballistic apps on iPhones, Kestrel weather stations with Horus Ballistics built in, 5.11 Tactical watches with Horus, and all manner of technical kit. It is possible to visit most of the modern ammunition manufacturers’ websites and find ballistic solutions which allow you to enter relevant data for your rifle, ammunition, the prevailing conditions and the destination, before printing out a chart providing the expected solutions. Hornady’s site also allows you to print out a small cheat sheet, to laminate and tape to your rifle, with quick solutions for range and wind out to 600m/y, which is very handy.

I have focused on range when describing how to adjust, but let’s not forget the major factor in misses at over 150m with a centrefire rifle – the wind. Setting the turrets to compensate for the wind is fraught with problems because the only constant thing about the wind is its variability. Set for range and, unless your target walks away, you are ready and prepared; at least out to perhaps 400m. Set for a measured 15mph crosswind, and you’d better hope it is still a 15mph crosswind when you shoot 30 seconds later, or you might miss by up to 43cm on the same 300m shot. Why? Because a 15mph crosswind affects our .308 150gr bullet as much as 290m of gravity… 43cm to the left or right!

We can adjust the windage for longer shots, but you have to fire under exactly the same conditions as prevailed when you held up your wind meter, before you adjusted the sight. When involved in management hunts which test my professional skills, I tend to set for range

and make small aim-off for the relevant wind at the moment of the shot, for best effect. If my aim-off takes me outside of the actual kill zone – as it would on the shot described above – I would need a very good reason before I made the shot.

I can generally judge the wind within two to three miles per hour, up to perhaps 20mph, by feel and observation in temperate climates with grass, trees and bushes around. In a high desert with only feel and mirage to go by, this becomes three to five miles per hour, up to perhaps 15mph. Beyond these parameters I need a wind meter, which only measures the wind where it is and when it’s up, not halfway to the target or round the corner from the rock you’re crouched behind; they are of limited use when hunting. I have been shooting long range for 40 years and I am still learning about windage.

More investment gets us into the current crop of range-finding monoculars, and binoculars with ballistic solutions built in. These vary from a few hundred pounds, to two or three thousand pounds. Leica’s flagship model is the HD-B, while my two favourites are the Leica Rangemaster 1600-B at around £700, and the Bushnell Fusion One Mile series at around £900. All of these can be found via the internet, with various offers from retailers from time to time to sharpen their appeal. There are products which provide similar solutions from Leupold, Hawke and others.

There are two common factors affecting their efficacy:

1) Can the owners work out how to use them properly?

2) None of them offer wind solutions, when wind is 50% of the problem in long-range shooting

The ‘nut behind the butt’ is the ultimate wind solution, and knowing what to do and whether to fire or not is an art with a lifetime apprenticeship attached to it. At WMS, we have a steady flow of clients who request training to enable them to understand and get the best out of the kit and ballistic solutions they have acquired, which is good for all involved.

In his poem An Essay on Criticism, Alexander Pope observed that ‘A little Learning is a dang’rous Thing; Drink deep, or taste not the Pierian spring’. Shooting at ranges over 200m is like this; you need to practise and learn a lot before you unleash your new-found theory on anything with a pulse.

Related Articles

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

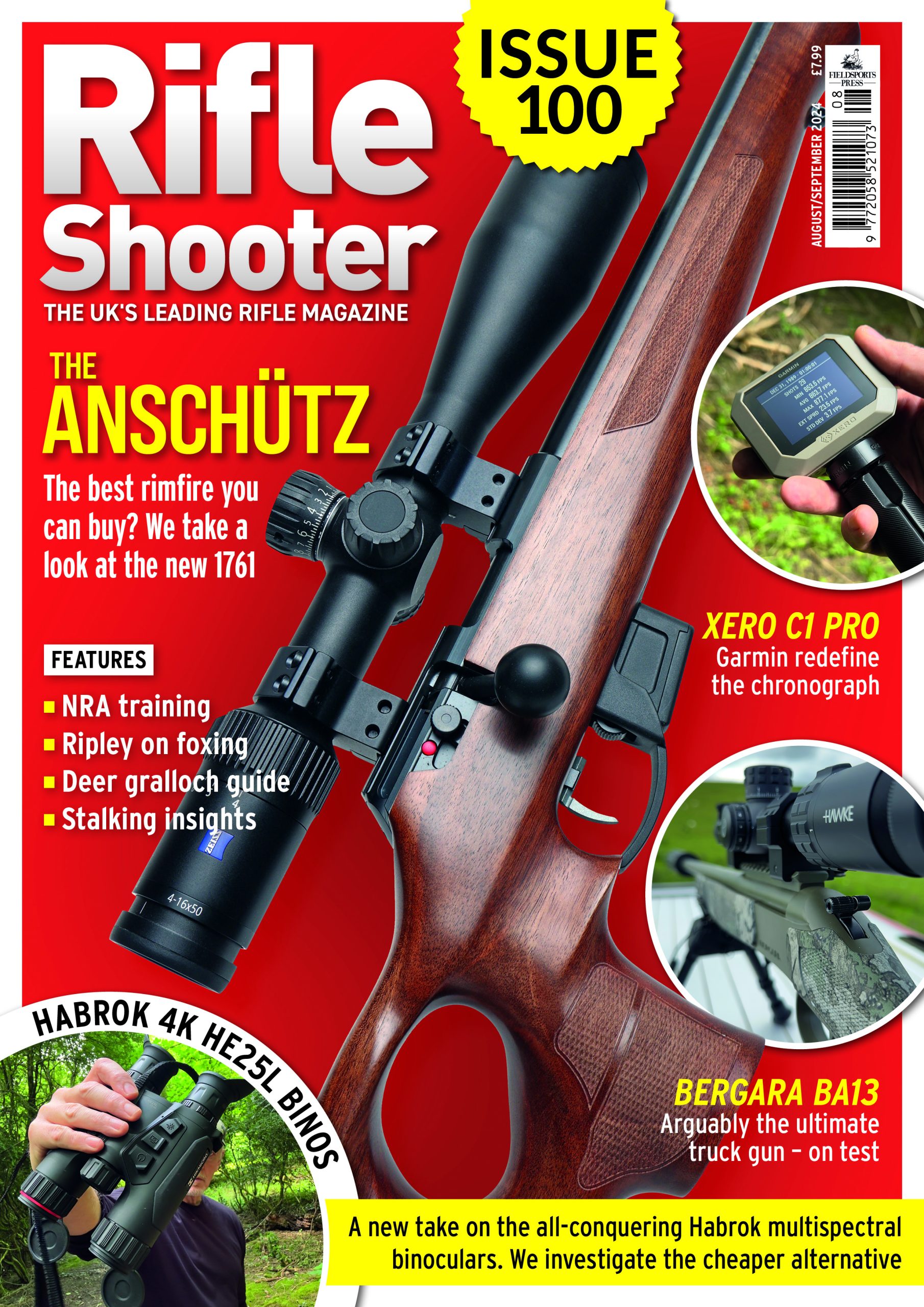

Subscribe to Rifle Shooter

Elevate your shooting experience with a subscription to Rifle Shooter magazine, the UK’s premier publication for dedicated rifle enthusiasts.

Whether you’re a seasoned shot or new to the sport, Rifle Shooter delivers expert insights, in-depth gear reviews and invaluable techniques to enhance your skills. Each bi-monthly issue brings you the latest in deer stalking, foxing, long-range shooting, and international hunting adventures, all crafted by leading experts from Britain and around the world.

By subscribing, you’ll not only save on the retail price but also gain exclusive access to £2 million Public Liability Insurance, covering recreational and professional use of shotguns, rifles, and airguns.

Don’t miss out on the opportunity to join a community of passionate shooters and stay at the forefront of rifle technology and technique.