Population and damage assessment for deer cull plan

Mike Allison from Jelen Deer Services presents a detailed guise to population and damage assessment when planning a deer cull

Management can be summarised as ‘achieving an objective using the information, manpower, means and equipment at your disposal’. The correct management of deer – regardless of the species – is dependent on reliable information and the accuracy of the data used. There is generally inconsistency and uncertainty in deer management throughout the UK, especially where the ‘management’ of deer is left solely to recreational stalkers. Management planning is often based on vague belief or fabrication of ‘evidence’, rather than on fact.

It is not uncommon for population numbers to be exaggerated – even ‘engineered’ – to give false impressions designed to justify a need for increased culling.

To form the basic framework from which a workable management strategy can be formulated, it is vital that there exists a clear understanding of the relationships between three principal factors: deer density, stalking activities and environmental impacts caused by deer. The understanding must be based on accurately recorded and reliable data, as this will influence what we need to do and how we do it.

Beginning to manage deer in a given area requires some form of scientific basis; this enables a sensible starting point. In many cases, the required information is either unavailable due to previous ad hoc ‘management’ of the animals, or is deliberately withheld by the previous ‘manager’.

Either way, you need to have some method of guiding your initial thoughts which will act as a driver in the formative stages of your management strategy. At Jelen Deer Services we feel that there is a drastic need to shift attitudes from simply deer population control, to wider management of the ecosystem in which the populations exist.

We feel that there is still far too much focus on the killing of deer, rather than the wellbeing of the environment in which they live, feed and breed. It is not unreasonable to assume that, in many cases, increased agricultural and forest crop damage occurs through deliberate design, rather than a consequence of un-checked population growth.

There is a serious need for deer managers and stalkers to start sharing information and encourage cross-boundary cooperation; however, this is unlikely to be achieved anytime soon.

So, for the time being we have to hope that we can continue to train, support and facilitate those that seek to manage deer in the interests of the landowners on whose land they operate, and not least in the interests of long-term sustainable crop yields and woodland biodiversity.

For many, the first stages of management are not only the most crucial, but the most stressful too. In this article we look at how to begin your management strategy through the use of available data, or at least some form of standard data usage that may help set you on the right track from the outset.

Where do we start?

Most stalkers and would-be deer managers are likely to begin with an attempt at finding out how many deer are on the land, and therefore the logical starting point would be to carry out a deer census or survey.

However, before embarking on any type of deer census it is wise to bear in mind that few – if any – yield results that can be relied on as a sound basis for management.

Unless they are carried out thoroughly, in a structured manner, using operatives that are competent in that type of work and meticulous in data-recording processes, then it is simply a waste of time and effort.

When done properly they can be time-consuming, as well as physically and financially challenging.

The aim of a deer census is to systematically acquire and record a range of information about the animals in a given population, over a particular area.

The information we would need to record would be:

n The number of breeding-age females – This would give us a clear indication of the minimum number of offspring that we could expect to be born in the following spring/summer, based on both census data and reproductive performance data from culled females.

n The number of fawns/calves – If carried out in March, then this number would determine calf/fawn survival rate, and therefore the percentage of offspring likely to be recruited into the herd from the remaining breeding-aged females.

n The number and age structure of males – It is important to aim to achieve succession in the males. In some cases – even in enclosed herds – it is not unusual to see several mature stags/bucks and a proliferation of young animals, but few middle-aged animals.

n The ratio of males to females – A sex ratio of 1:1, male:female, would be ideal. This is the usual ratio at which offspring are born. However, this is rarely achieved in reality.

The assessment of herd reproductive performance can be reinforced through keeping detailed records of reproductive status in culled breeding-aged females.

In an ideal world, the recorded data should provide an accurate assessment of deer numbers, sex ratio, and age structure, with the aim of using the information to formulate a detailed, meaningful cull plan for the following year.

However, a deer census that is accurate enough to aid such detailed cull planning would rely on:

n The herd being closed – No immigration or emigration takes place. There are many influences on population dynamics over which we have absolutely no control, and depending on the specific event, the movement of animals into and out of an area can occur literally in minutes.

n Sighting likelihood remaining constant – The probability of animal observation would need to be constant, at least during the data collection period. The varying types of cover in the UK make this virtually impossible.

n All animals equally susceptible to being observed – Animals of each species, sex and age must be susceptible to counting. The differing operational environments and animal behavioral characteristics would, again, make this almost impossible.

n The total number of observed animals equalling the total number present – Due to the range of variables, there would be no way of knowing this in the wild.

In view of the above, the only time we would be able to achieve total accuracy in a census would be on an enclosed herd (i.e. on a deer park). We can safely conclude that, in most cases, a deer census aimed at establishing an absolute and accurate count of wild deer is more a case of wishful thinking than a realistic possibility.

Having said that, where census data is used in conjunction with other forms of population and impact assessment, then it can help to establish trends, show patterns of land usage by the deer, and reinforce the results of other methods of direct and indirect population assessment.

Timing and Methodology of Census Work

Where census work is the preferred method of herd assessment, then the ideal time to do this would be in March. At that time of the year there the least natural cover, which would therefore aid direct observation of animals.

All animals that are present at that time are likely to be ‘survivors’, given that the doe/hind cull would have been completed, and deaths through the impact of winter and natural mortality would have already occurred.

However, it must be understood that direct observation of animals will only provide an absolute minimum number of animals that were observed at that moment in time. Even the very act of census work can, in some cases, cause rapid movement of animals off the property – especially where fallow are concerned.

Careful planning of the operation, as well as careful selection of observers, is crucial to achieving a realistic ‘picture’. Placement of observers needs to aim for maximum area coverage from each operator. In this case, carefully sited high seats are ideal. Observers should be placed in high seats well before first light.

The weather conditions can cause many problems for the observation team, especially in windy weather where sighting likelihood is reduced, and can result in widespread clearance of an area through the windborne scent from observers. Therefore, it is worth looking at long-range forecasts, and planning census work for when weather conditions are stable.

Observer Experience and Capability

Each observer should ideally be an experienced deer manager/stalker who is able to remain observant for at least two to three hours; but, more importantly, they need to be able to record accurately what they are seeing – not just the numbers of deer, but the sex and age structure, too.

Video can be a useful tool to use in these cases, especially since carefully obtained footage will have a time signature, and can be studied by an experienced deer manager at his/her leisure.

Other forms of observation techniques, such as Infra-red Night Vision (IR) and/or Thermal Imaging (TI) equipment, can be very useful, but still require the observer to know what he/she is looking at, and be able to record it accurately.

While both IR and TI technology can highlight the presence of deer, only the most experienced operators would be able to distinguish between a young, middle-aged or old deer. Even establishing the sex of an animal can be almost impossible, except in exceptional circumstances.

With TI in particular, stags/bucks in hard antler would not be easily noticed, as hard antler is cold and therefore gives off no heat signature; although the experienced eye can sometimes pick up the faint outline of hard antlers. The limited magnification on TI equipment can also cause difficulty in establishing the sex. It must also be appreciated that TI equipment is virtually useless in foggy or rainy conditions.

What information do we need from our census?

In order to accurately plan a cull, the information we need to acquire from a census would ideally be as near as possible to an accurate figure for the following:

? Area (in hectares)

? Number and age structure of males

? Number and age structure of does

? Number of fawns/kids/calves

? Total number of deer

? Percentage of fawn/kid/calves surviving

? Male/female ratio

? Hectares per adult deer

? Deer per hectare total

Management Planning

There is a general belief that the deer census data forms the key foundation of the culling and management plan. This is rarely the case. While the data may form an important aspect of it, there are many other considerations that need to be addressed. Other influences on management planning would include:

n Assessment of current deer condition – Generally speaking, the higher the density, the poorer the overall condition of the deer will be. Often this is manifested in the carcass weights of culled deer. If data is recorded annually, it is possible to observe progressive change and to correlate this with random sighting and impact assessment data, be it positive or negative.

n Nutritional value of feed and quantity available – As one of the three vital requirements for a deer’s desire to live somewhere, feed quality and quantity will influence the level of impact that can be expected on crops and trees in the area. The amount and quality of feed available, and deer density, is generally reflected in body condition and antler development. Effective monitoring of body mass parameters in culled deer should correlate with impact assessment results.If insufficient natural feed is available, then it can safely be assumed that the adverse impact on crops will be elevated, and it will be reflected through impact assessment.

n Quality of the environment – Where there is adequate natural feed availability, shelter from the elements, security and relative freedom from disturbance, then such an environment will undoubtedly support a greater number of deer. In this case, the carrying capacity can increase without necessarily being detrimental to crop yields.

n Other land-use considerations – The Deer and Wildlife Manager (DWM) will need to establish which other forms of land use can be expected, including the possibility of high public access. On designated lands, or where vulnerable high-value crops are produced, regular detailed monitoring will be necessary to identify an increase in damage before it begins to threaten crop yields or biodiversity.

n Long and short-term owner objectives – Establishing owner objectives at the outset of the management programme is vital, as this will shape the management plan going forward. Where there is a failure to achieve owner objectives in the short term, the DWM’s long-term involvement will almost certainly be jeopardised.

n External influences – Understanding cropping systems and other factors or events that occur off-boundary is important for predicting influxes or emigration of animals affecting the core area.

The possibility of cross-boundary cooperation should be investigated early to help minimise adverse impact potential, and to encourage more effective management. This may well mean that all owners concerned have to accept some level of compromise in order to achieve efficient management.

Impact Assessments

Of the various methods used to establish deer density and population levels, impact assessments (IAs) provide the most reliable ‘picture’ indicating the effects of deer presence on their environment. However, IAs are only useful if carried out with care and consistency.

For the assessments to make sense, each assessor should be trained in the correct procedures, but equally important is the ability to correctly measure and log the particular assessment criteria to a standardised format. Where there are inconsistencies, then variations in IA results will occur, and consequently the assessment is unreliable.

It is important that all operators are trained and that measurement techniques and plotting methods are consistent throughout the team.

Impact assessments should be carried out on a yearly basis, preferably during March to May when observation of deer signs is easier, but more importantly the observed sites need to be the same sites each year. That way a true indication of impacts will be established.

Impact assessments currently being carried out in the UK largely involve random and uncoordinated inspections that are subjective in nature. In most cases the observer/s simply wander about the woodland ‘looking’ for signs of deer presence, be it paths, physical damage, droppings or actual sightings.

The very nature of this method suggests that the more experienced the observer is, the higher the relative ‘impact score’ would be, due to the fact that the experienced observer would be able to find more ‘signs’ than the less experienced operator.

The problem with this system is that the results are subjective and prone to significant variability, depending on who carries out the assessment and, more importantly, how they score it. This has been proven by examining the IA scores carried out by three individuals assessing the same area on the same day.

The impact assessments that are carried out by the team here at Jelen Deer Services are recorded in a different manner, using ForestTrack. ForestTrack is a high-tech system utilising EID (Electronic Identification)technology and Wi-Fi to ensure that recording processes are consistent, measurable, and therefore more reliable. This multi-purpose system is also used for risk assessing and monitoring maintenance programmes for high seats.

Impact assessment scores are recorded on the supplied form, complete with advisory notes for the operators. The recorded data can be compared year on year to establish the level of grazing pressure on the exact same plots. When correlated with other population assessment methods, a more realistic assessment of grazing pressure will be achieved.

Methodology

The assessor should plan a transect line of at least 1.5km in length, encompassing as many of the varying types of cover in the area which will be assessed.

Over the 1.5km line there needs to be 50 stops, each 30m apart, known as stop sites. Each stop site should be clearly marked with an EID tag, or other clearly visible marker, so that the exact same area can be located in the future. Each stop site should be a 1m x 1m square, and the assessment of deer impact should only be measured within that square.

Using the basic IA scoring system several elements are examined and scored according to set criteria. The scoring for each element is clearly detailed on the IA recording sheet, so scoring should be uniform regardless of who carries it out. Naturally, this is dependent on each assessor being trained in exactly the same way.

When inspection of the 50 stop sites has been completed, then the assessor will have examined in detail a complete 50 square metre area, across the entire assessment area.

Using ForestTrack, the exact same area can be measured year on year with ease, and the system will alert the assessor if any information is missing.

Related Articles

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

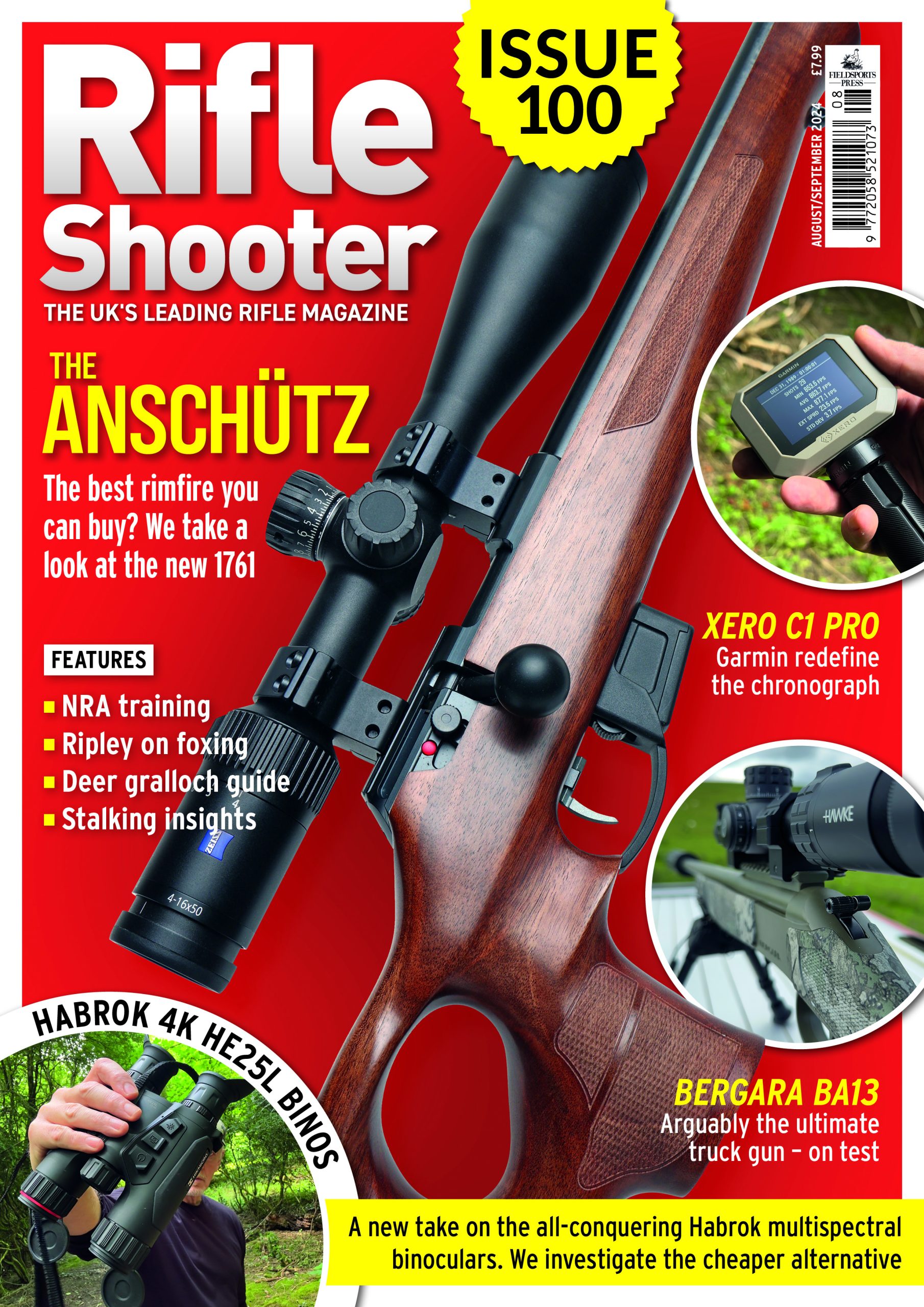

Subscribe to Rifle Shooter

Elevate your shooting experience with a subscription to Rifle Shooter magazine, the UK’s premier publication for dedicated rifle enthusiasts.

Whether you’re a seasoned shot or new to the sport, Rifle Shooter delivers expert insights, in-depth gear reviews and invaluable techniques to enhance your skills. Each bi-monthly issue brings you the latest in deer stalking, foxing, long-range shooting, and international hunting adventures, all crafted by leading experts from Britain and around the world.

By subscribing, you’ll not only save on the retail price but also gain exclusive access to £2 million Public Liability Insurance, covering recreational and professional use of shotguns, rifles, and airguns.

Don’t miss out on the opportunity to join a community of passionate shooters and stay at the forefront of rifle technology and technique.