Reloading – case trimming (essential for fired brass)

Spud (our reloading expert) looks at the different methods and tools we can use to cut the cases we will be reloading down to the correct length

Once you have shot your brass a few times, in most calibres with standard shoulders the brass case will increase in length due to brass flowing forwards, due to the firing procedure of the round. Some calibres, such as the Ackley Improved variants that have 40° shoulders, don’t tend to lengthen too much or as often, so trimming them isn’t such an issue.

In the standard calibres we have to trim because, as the case gets longer with the brass flowing forwards, the case will end up too long to actually chamber in the rifle. So, we trim the case back to a set distance to give us clearance in the chamber. The length we trim back to is called the ‘trim length’. Brass case manufacturers like Lapua, Norma and Nosler all produce recommended trim lengths on their websites for certain calibres. We can also trim to the shortest case in a batch. The way we go about this is to measure a selection of brass in our batch (at least 10) and find the shortest case, then trim the rest to that length. This is also a good time to carry out a case inspection, looking for any defects such as splits, dents or anomalies. All trimmers trim the neck end of the case.

There is no set rule as to how often cases should be trimmed to length. Some calibres will need trimming more frequently than others. If you are using a ‘pokey’ load, and by that I mean a load that is near the top end of the pressure range, brass tends to flow more and so the cases will need trimming sooner. One issue to be aware of when continually trimming brass is that the brass in the web section of the case (where the case head thins into the body) can become too thin and cause the body of the case to separate from the case head; this can happen after many firings and trims. This is called ‘head separation’. If you notice it, discard the case. It can usually be spotted by a faint ring around the circumference of the case in the web section.

Once the trimming is done we must remember to chamfer the inside of the neck and deburr the outside before going any further. I personally like to trim a fired case before I have resized it, but hey, we all do it differently.

There are a few different ways to actually trim your brass. Starting at the cheaper end, we have Lee Precision’s Case Length Gauge and Shell Holder, which allows you to screw a set length gauge for a certain calibre into a cutter and trim to the set length. It’s designed to bottom out on the shell holder when the length is reached. Lee Precision’s other option is the Quick Trim Die, where you place a brass case inside a calibre-specific trim die, and then place the die into a standard reloading press. Then, with a handheld cutter, you trim the case down using the trim die to set the length.

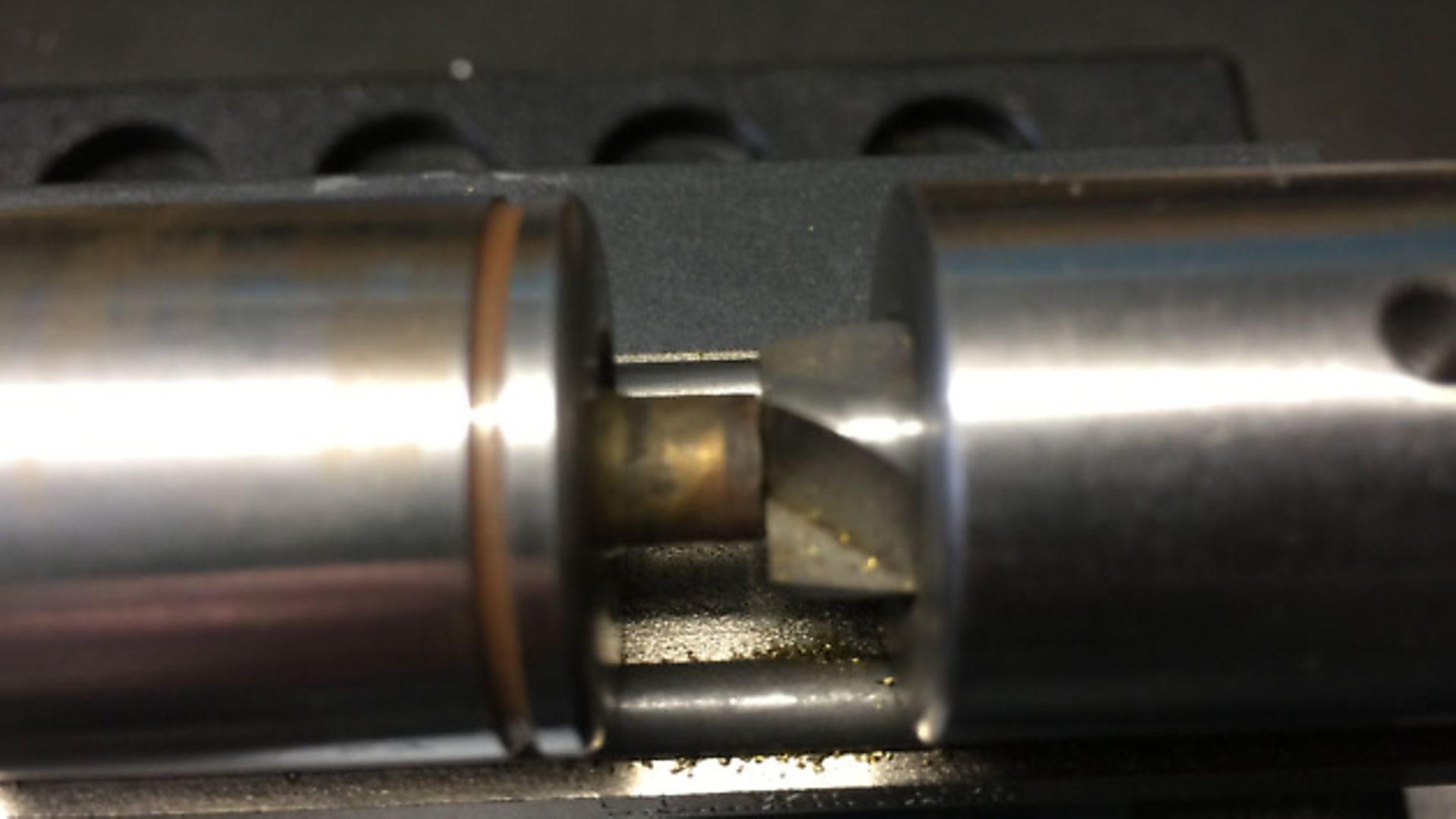

Moving up the expense scale we start to see lathe-type trimmers appear from most of the mainstream manufacturers. These hold the case by the case head using a collet, and the cutter is guided by a pilot into the neck where it starts cutting the neck down. Some of these types of lathes, such as the Forster, can also double up as outside neck turners, and most will also handle inside neck chamfering as well.

As the cost of the trimmer increases, so too does the range of accessory options, which include things like micrometer gauges for ease of use when setting custom case lengths. You may use these for trimming your brass to the shortest case in the batch. The micrometer-type attachments help to make minute alterations to trim length, and also aid repeatability when using the trimmer from session to session, as you can note the actual settings on the micrometer. Some of the more custom-grade trimmers, like the LE Wilson, dispense with a collet for holding the case and instead use a case holder. This is a short piece of round bar with a calibre-specific hole in the middle in which the case is placed and tapped home for a tight fit. The case holder is then placed onto two rods on the trimmer bed, and a clamp is employed over the top to hold the complete assembly in place.

Other types of trimmers are the ones that can be used in conjunction with a battery-operated power drill. These have a hex shaft rod on them that the drill bites onto. These usually slip over the top of the case neck and trim the neck down until a built-in stop hits the shoulder and bottoms out the cutter. Slight variations on this type of cutter also allow us to trim, deburr and chamfer the neck at the same time, all in one operation. As already mentioned, some trimmers also allow us to neck turn with outside neck turning attachments, and others allow us to use inside neck reamers for the removal of internal ‘donuts’ (this will be covered in more depth in a future issue).

There are pros and cons to all of the above trimmers. Some will only cut to a set length and therefore are not as adaptable as others. Some are calibre specific so you will need to get a few different cutters if you shoot a few different calibres. Some are just more expensive than others. Like most tools in the reloading world, it’s a very personal choice as to which one you use, and to a certain extent the type of shooting and calibre used can determine the type of cutter you might use.

There is no such thing as a bad trimmer, but some features are more desirable than others – for example, to be able to hold the case in a case holder while trimming leaves both hands free for ease of operation.

Related Articles

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

Subscribe to Rifle Shooter

Elevate your shooting experience with a subscription to Rifle Shooter magazine, the UK’s premier publication for dedicated rifle enthusiasts.

Whether you’re a seasoned shot or new to the sport, Rifle Shooter delivers expert insights, in-depth gear reviews and invaluable techniques to enhance your skills. Each bi-monthly issue brings you the latest in deer stalking, foxing, long-range shooting, and international hunting adventures, all crafted by leading experts from Britain and around the world.

By subscribing, you’ll not only save on the retail price but also gain exclusive access to £2 million Public Liability Insurance, covering recreational and professional use of shotguns, rifles, and airguns.

Don’t miss out on the opportunity to join a community of passionate shooters and stay at the forefront of rifle technology and technique.