Rewilding: impact on deer management & communities in rural Scotland

Niall Rowantree explores the impact of the rewilding movement on deer management, conservation and rural communities in Scotland… Few of the deer stalkers who are regular readers will have failed to notice the politics surrounding all forms of unregulated hunting that we currently enjoy. Seldom a day passes without an article in the press accusing

Would you like to appear on our site? We offer sponsored articles and advertising to put you in front of our readers. Find out more.

Niall Rowantree explores the impact of the rewilding movement on deer management, conservation and rural communities in Scotland…

Few of the deer stalkers who are regular readers will have failed to notice the politics surrounding all forms of unregulated hunting that we currently enjoy. Seldom a day passes without an article in the press accusing hunters of cruelty or threatening the existence of native species – even though the reality is considerably different.

The fact that hunting is a culturally and economically important pursuit for many human populations across both the developing and developed regions of the world has been lost from sight. The fact that hunting provides an important food for human populations from Cape Wrath to Canada and from Argyll to Scandinavia is overlooked.

In Scotland, hunting is rooted in cultural tradition and involves customary rights, generates jobs and incomes, provides broader benefits for local people and raises critical funding for conservation and management. It is a highly valued recreational experience. There are crucial governance issues involved, particularly the rights of local communities to choose how to manage their wild resources and meet their livelihood needs.

Although hunting is considerably less popular with mainstream society today than it used to be, the science is pointing for this practice to continue and that, indeed, it is essential to delivering wider national landscape objectives. Across much of North America and Europe, an increase in deer numbers has affected biodiversity and many visions of what our landscapes should look like – and, even in environments where large predators have been reintroduced, the role of man as a hunter has been shown as essential in keeping populations in balance.

Effective deer management

In the majority of forest habitats in the UK and Europe, deer numbers are rarely assessed effectively and management is mainly based on impact. Even in areas where management has achieved stable levels of impact, there is still insufficient understanding of the relationship between damage and density. It goes without saying that every grazing and browsing animal will have an impact, and your objectives will define to what extent it is unsustainable damage or not.

Simply put, different habitats do benefit from differing levels of browsing or grazing, so species-rich grassland may benefit from grazing pressure of 6 to 8 animals per square kilometre and this may maintain that habitat in a favourable condition. However, further down the same hillside, native woodland may be struggling to regenerate if densities are above 4 animals per square kilometre. As if this wasn’t complicated enough, the influences of the changing climate are also playing its part in the form of late spring weather, increasing rainfall or prolonged periods of poor weather keeping animals in sheltered areas.

For the majority of deer managers and farmers in the Highlands, different requirements for different habitats are well understood and in recent years, the wild red deer herd in the open range has been stable due to collaborative deer management in action delivering high levels of cull through the voluntary approach by landowners and stalkers. The deer management groups have worked hard to manage their deer populations to balance credible habitat objectives.

The question now is, will it be enough as the goalposts start to move again? Increasingly, the rhetoric has moved to landscape restoration which some call rewilding rather than deer management. This desire to rewild is to transform our landscapes, bringing back the native woodland and its associated wildlife.

Woodland regeneration in Scotland

With woodland restoration being a priority, the rural community is bracing itself to face a new suite of buzzwords like ‘natural capital’ or ‘nature-based’ solutions. Government is making huge commitments to expanding woodland cover and many rural communities believe that, right or wrong, much of this will occur in the uplands and probably on the edge of the existing peat or moorlands.

In August 2019, the Scottish Environmental Link, which makes up the majority of conservation charities in Scotland, announced a number of benefits that could be delivered by less deer. These included: more trees, healthier peatlands, more rural jobs, reduced rural inequality, a reduced need for fencing, safer rural roads, improved deer welfare, a stronger venison industry and highlighted that red deer are responsible for the production of 5,500 tons methane

each year.

They went on to state that in their combined opinion, “the current system of deer management in Scotland is unique in Europe. In most other countries, deer hunting is closely integrated with other land uses, involves a larger number of recreational hunters, and is highly regulated – with culls set and monitored by local or national authorities to ensure the protection of the natural environment.

“None of that applies in Scotland. There is no statutory regulation of numbers. In the absence of those natural predators that were previously wiped out by humans, it is effectively left to individual landowners to decide how many deer are culled, and who can or cannot participate in hunting. Our ‘deer forests’ – which despite their name are notable for the stark absence of trees – have long been controversial, with many experts over many decades questioning the wisdom of devoting a huge proportion of our land mass to a single activity.

“After generations of inaction from successive governments, there have been welcome signs in the past few years that the government is showing a willingness to face up to the need for change. If we act now, we could shape a modernised deer management system fit for the 21st century and start to build a brighter future for our natural environment and for our rural communities.”

Although we could spend a few minutes pointing out that the term ‘forest’ actually has its origins in wildlife and doesn’t refer to trees at all, the direction of travel is quite obvious to anyone following the debate.

To deliver this level of restoration or expansion, particularly of woodland, it is likely that significant changes are around the corner. With the move to a landscape vision, the challenges for everyone are likely to expand significantly. At the current time, most woodland objectives are delivered behind deer fencing, with the notable exception being funded by external wealth invested by well-meaning non-resident individuals.

If habitat restoration and the maintenance of a deer population below their current levels is to be delivered, very credible funding mechanisms have to be found. Some believe this will be through payment for the delivery and maintenance of natural capital or through carbon offsetting funds.

Lessons to learn

Whichever routes are chosen, there will, no doubt, be lessons learned. The move by the national estate in the guise of Forest and Land Scotland toward a contractor-based system is evidence of the cost implications. If the funding does not keep pace with expanding woodlands and improve the habitats for deer, the likelihood is that the whole thing will very quickly run away from us all.

Interestingly, the conservation lobby believe that dismantling the current system, and its funding mechanisms, will deliver a modernised approach to deer management. Frequently, we hear reference to other countries in Europe, like our wealthy neighbour Norway, as a model that Scotland should emulate which presents its own challenges and the need for further scrutiny.

In common with other parts of Europe, Norwegians have seen a large increase in red deer numbers with the total harvest in 1970 of around 2,800 animals rising in 2009 to 39,000 animals. The increasing numbers of red deer harvested is significant as Norwegian attitudes to hunting are very different to Britain. For example, the results of a 2008 survey indicated that 74% of the population thought hunting was an acceptable activity.

There are over 500,000 registered hunters in Norway which is almost 12% of the total population and of this more than 140,000 are considered active. If a culture that approves of hunting finds deer increasingly challenging and costly to deal with, we do well to take note and plan accordingly.

If these sorts of figures are to be achieved in the United Kingdom which will be the minimum to protect expanding woodland objectives, then a national campaign is going to be necessary to expand total numbers taking part in active deer management. Training opportunities and funding to support this is likely to be a key component.

Already in many parts of Scotland and other parts of the UK, one of the biggest changes in deer density is an expanding range and already significant populations of roe deer exist in parts of the country that they were absent from a few short years ago. Now red deer and sika deer are following suit expanding into new areas as can be seen by the colonization of Aberdeenshire by red deer in recent years.

This vision of the new landscape for Britain is going to need to blend sustainable agriculture with a more diverse landscape which underpins rural communities and creates an environment to deliver our increasingly prescriptive vision of food production. Our wildlife will need to be carefully managed to enable it to cope with the challenges to come. In my mind, one thing is for sure, the hunter will play a part as abdication will simply not work on this little island we inhabit.

Related articles

AN ICELANDIC SAGA

Niall Rowantree explores the impact of the rewilding movement on deer management, conservation and rural communities in Scotland… Few of the deer stalkers who are regular readers will have faile...

By Time Well Spent

AFFORDABLE INNOVATION

Niall Rowantree explores the impact of the rewilding movement on deer management, conservation and rural communities in Scotland… Few of the deer stalkers who are regular readers will have faile...

By Time Well Spent

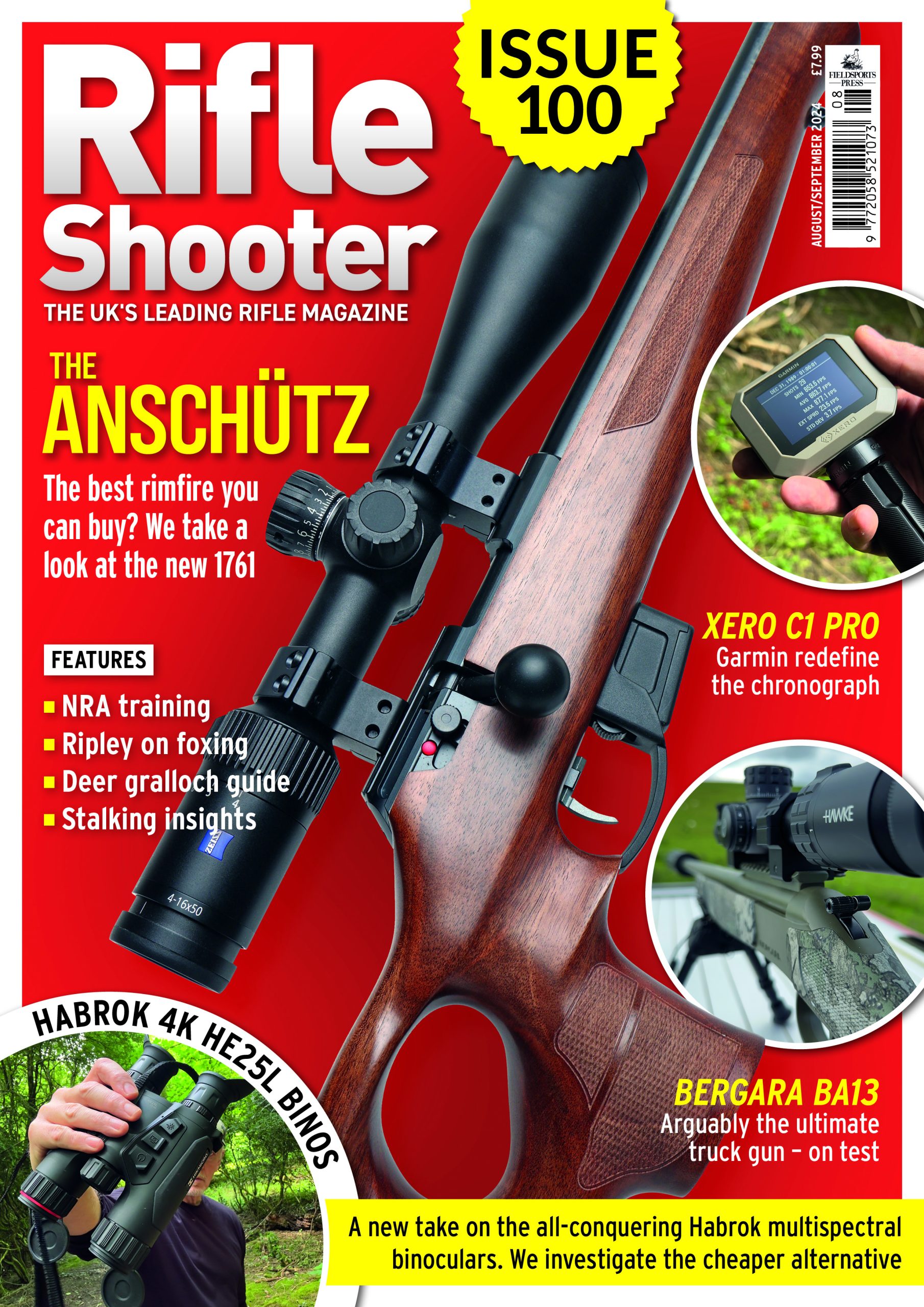

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

Subscribe to Rifle Shooter

Elevate your shooting experience with a subscription to Rifle Shooter magazine, the UK’s premier publication for dedicated rifle enthusiasts.

Whether you’re a seasoned shot or new to the sport, Rifle Shooter delivers expert insights, in-depth gear reviews and invaluable techniques to enhance your skills. Each bi-monthly issue brings you the latest in deer stalking, foxing, long-range shooting, and international hunting adventures, all crafted by leading experts from Britain and around the world.

By subscribing, you’ll not only save on the retail price but also gain exclusive access to £2 million Public Liability Insurance, covering recreational and professional use of shotguns, rifles, and airguns.

Don’t miss out on the opportunity to join a community of passionate shooters and stay at the forefront of rifle technology and technique.