Sako 6 species – muntjac fact file

Everything you need to know about muntjac deer, including habitat, appearance, antler formation, behaviour, breeding/reproduction, and the legal shooting seasons

Species history, population and distribution

There are at least seven known species of muntjac. Reeves’ muntjac, the species found in abundance throughout much of southern England, is an introduced species native to South Asia. It is generally accepted that our current population descended from the escapees of Woburn Abbey Deer Park. The then Duke of Bedfordshire, who lived at Woburn, imported a small population pre 1900 which flourished and rapidly spread into the surrounding areas. Records of small colonies outside of the main areas suggest that some human releases may have also contributed to the population; muntjac are listed as a non-native species and their release is prohibited under Section 9 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981.

A study from 1995 estimates the UK population of muntjac at 40,300. Dense populations are found across southern and central England and Wales, with a patchier spread towards the north that comes close to the Scottish border. Similarly to rabbits, muntjac breed all year round; this has contributed greatly to their rapid spread and vast population. Graphs displaying bag densities from 1980 to 2009 show an average gain of 12% per annum, reflecting the swift and ongoing expansion of this species.

Appearance, antler formation and behaviour

Reeves’ muntjac are small and stocky. Their haunches are taller than their withers, giving them a hunched appearance, and they have a fairly wide tail with a pale underside which is held erect when disturbed. Males grow to 44-52cm and weigh 10-18kg, while females grow to 43-52cm and weigh nine to 16kg. Their coat is russet-brown in the summer and grey-brown in winter. They have a ginger forehead, and the males sport two prominent black lines starting between the eyes and running up the pedicles; females show a dark diamond-shape on the forehead with less ginger visible. Two large pairs of glands are visible on the face: the ‘frontal glands’ sit between the eyes; the ‘sub-orbital glands’ sit below the eyes and look like extensions of the inner corner. Both sets of glands are used to mark territories and boundaries by rubbing/wiping the secretions on vegetation and trees, with the sub-orbital glands becoming more dilated during times of excitement, such as mating. Both sexes have tusks protruding from the upper lip (though they are smaller and sometimes not visible on females) suggesting they are a primitive species; prehistoric evidence of muntjac has been recorded, affording them the title of the oldest known deer species.

The males have short, usually un-branched antlers protruding from long pedicles; a brow tine or point can occur in some older bucks. The antlers are shed in May or June, and regrow by October or November; like other species they are covered in velvet when growing, which is then rubbed off on trees, etc. Antlers tend to be around 10cm or less, and they are not used during combat when rutting like most other species. Instead, muntjac will use their tusks in battle.

These small deer prefer to inhabit deciduous or coniferous forests, ideally with a diverse understorey, but are extremely adaptable and can also be found in scrub and urban gardens. In high-density populations they often create networks of tunnels in thicker vegetation. They are browsers, not grazers, and enjoy a varied diet of bramble, ivy, flowers, shoots, and seeds from many plants. Consequently, they do not cause much agricultural damage, however they do cause significant damage to gardens, coppiced woodlands and sometimes forests. They usually feed alone or in pairs, and higher numbers seen feeding together will usually be the result of a shared food source. Both bucks and does are territorial and muntjac are generally seen as single animals, but can sometimes be found in pairs (usually a doe with a kid, or a doe with a buck). Bucks will defend small exclusive territories, while the does’ territories will overlap those of other does and bucks. They tend to be active during the day and when undisturbed can be reasonably predictable, with bucks tending to patrol similar routes each day.

They are known as the ‘barking’ deer, as they produce short, loud barks like a dog when searching for a mate, defending territory, or when alarmed. Does and fawns are more inclined to make squeaking noises, and scream when distressed.

The rut and reproduction

The muntjac is peculiar in that it is the only UK deer species that breeds all year round, meaning there is no defined breeding season, or rut; this is due to their geographical origins in warmer climates. Bucks may fight for access to does but remain surprisingly tolerant of other males within their vicinity, unlike the larger species who will fight, sometimes to the death, to defend the does in their territory.

Muntjac does are polyoestrous and have a post-partum oestrus; this means they come into season and can conceive again only a few days after giving birth, and will cycle again after approximately 14 days if they fail to fall pregnant. In reasonable conditions the does can produce a single fawn every seven months, giving birth at any time of the year after a gestation period of seven months. Fawns will be weaned by six to eight weeks, with most mothers ceasing lactation by the time the fawn is around two months old. The fawns will be entirely independent by the age of six months. Young does weighing 10kg or more are capable of breeding, usually at around seven months.

SHOOTING SEASONS

Muntjac can be shot all year round due to their capacity to breed all year round; there is no ‘closed’ season. For humane reasons, do not shoot does that do not appear pregnant or those that have visible udders, as they are likely to be suckling a small kid. Heavily pregnant does will not have any dependants and so make a more humane target, as do yearling does because they will not have a fawn at foot. If a fawn is unintentionally orphaned, they will usually return to their mother within minutes of the shot being taken, and should then be culled, again for reasons of humaneness.

Related Articles

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

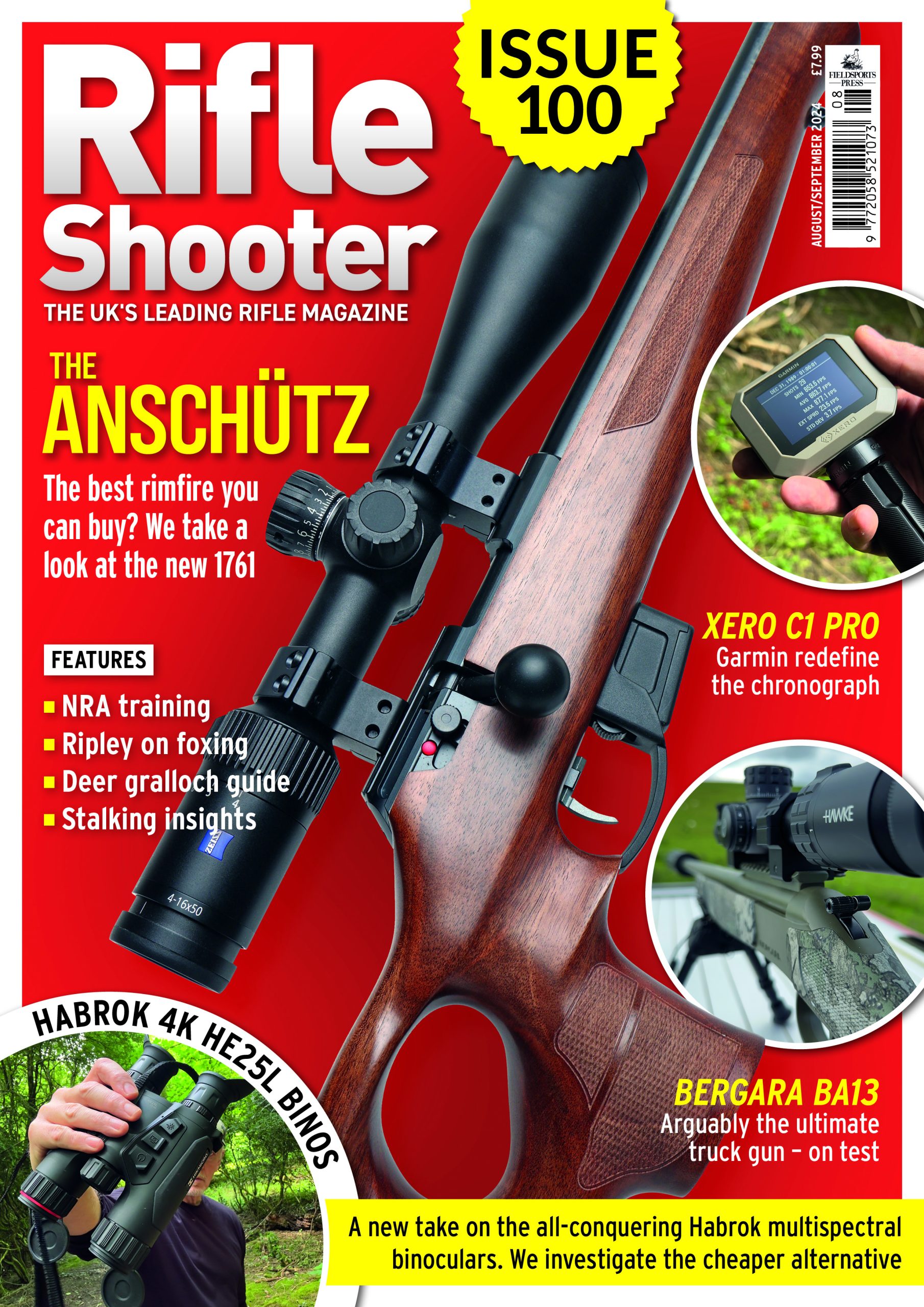

Subscribe to Rifle Shooter

Elevate your shooting experience with a subscription to Rifle Shooter magazine, the UK’s premier publication for dedicated rifle enthusiasts.

Whether you’re a seasoned shot or new to the sport, Rifle Shooter delivers expert insights, in-depth gear reviews and invaluable techniques to enhance your skills. Each bi-monthly issue brings you the latest in deer stalking, foxing, long-range shooting, and international hunting adventures, all crafted by leading experts from Britain and around the world.

By subscribing, you’ll not only save on the retail price but also gain exclusive access to £2 million Public Liability Insurance, covering recreational and professional use of shotguns, rifles, and airguns.

Don’t miss out on the opportunity to join a community of passionate shooters and stay at the forefront of rifle technology and technique.