The countdown is on for The British Shooting Show – book tickets online today and save on gate price!

The importance of rifle fit & avoiding ‘free recoil’

Free recoil when rifle shooting can have painful consequences, not to mention affecting your ability to shoot accurately; Andrew Venables from WMS Firearms Training tells us how to avoid it

People who hunt with rifles usually, though not always, have portable guns designed to be carried miles and shot sparingly. Most of these rifles have moderators, giving the shooter the benefit of noise and recoil reduction. However, some people still shoot un-moderated rifles, which in my opinion makes their shooting life harder than it needs to be.

All forces are equal and opposite, according to Newton’s Third Law (or, FA = –FB if you prefer). The Third Law states that all forces between two objects exist in equal magnitude and opposite direction: if one object (A) exerts a force (FA) on a second object (B), then B simultaneously exerts a force (FB) on object A; the two forces being equal in magnitude and opposite in direction.

Free recoil

Watching many different people shoot rifles means I often see the effects of this simple fact. Recently, despite constant reminders and observation, a chap I was with got caught on the nose and eyebrow by a scope on a rifle in free recoil. I can empathise because I have three scars above my right eyebrow from similar interactions over the last 45 years. So, what is ‘free recoil’?

Free recoil is what happens when a rifle is held insufficiently firmly to control and restrain its backward movement just after the bullet exits the barrel. The heavier the bullet, the larger the powder charge, the higher the velocity, and the greater the force. Free recoil is made worse by the tendency for people to ‘pet’ their rifle, rather than to grip it properly.

Rifles held loosely – petted – with space between the shoulder and buttpad and the cheek and comb, rapidly leap to fill the space when in free recoil. The discomfort caused when the accelerating rifle meets yielding flesh makes the user back off even further for the next shot… which causes even more pain and also spoils the results of the actual shooting.

I believe the tendency to try to shoot tiny groups from shooting benches using bipods, sand bags and all manner of support is causing people to lose grip of their rifles when using shooting positions for hunting. The floppy grip and gun petting I see seem to result from chasing one-hole groups.

A common ailment

I recently assisted on a weekend range event run by Blaser Sporting at Braces Shooting Range in Bristol. I was running a 100m firing point, with clients using shooting sticks from the standing position. I needed to encourage around 90% of the 140 people I assisted to hold their rifles more firmly at the pistol grip and fore-end, with universally positive results. My colleagues Helena and Ian, running the 200m firing point, reported the same issue in the majority of shooters. When we added the advice to set the jaw and cheek more firmly against the comb of the stock, results again improved. Once correct trigger control was incorporated with the use of the centre of the pad on the first digit, the triangle of correct support, restraint and release produced results which made people smile and come back for more.

No shots were fired until the correct position and technique were seen to be in place during dry firing. Attendees at the event fired four to six shots in each session, with most coming back again and again to try to improve further. The steel roe target, which was repainted half a dozen times during each day, was testament to the success of the exercise. The chest kill zone we highlighted in white was turned black by hundreds of shots. The only shots outside the kill zone appeared to be small groups shot deliberately by people wanting to record their success elsewhere on un-battered fresh paint.

Clients complaining of previously sore shoulders and cheeks quickly found the solutions to their woes; shooting results soared, and all because they reclaimed control of the .308 rifles being used over the weekend. If you don’t want to be bullied by your rifle, be firm with it, as discomfort will eventually lead to flinching.

Making a monster

Flinching is the anticipation of likely pain, manifested by a reaction prior to the event. If you blink when you squeeze, or more likely pull, the trigger, it is not because you are a failure; it is because you are alive, intelligent and aware that there may be discomfort coming. A blink is a baby flinch. It does not take much for the baby to grow into a monster.

Sudden loud noises cause discomfort, potential hearing damage and eventual or possibly instant deafness. I am writing this listening to tinnitus, caused by a combination of agricultural work, motorcycle riding and a lifetime of shooting. I have actually always worn hearing protection when clay shooting and target rifle shooting. Alas, I did not always wear it when rough shooting, wildfowling and hunting.

My generation did not have access to the brilliant electronic earmuffs and ear plugs, which have become available over the past 15 to 20 years. How I wish we had! So why, when attending larger events, do I end up trying to communicate with people who turn up with either foam disposable plugs, passive factory-type muffs, or nothing at all? A decent pair of entry-level electronic muffs costs £40 to £60. A really good pair costs £90 to £140, and fitted digital electronic ear plugs start at around £300.

People who don’t wear proper electronic hearing protection tend to flinch, don’t often shoot well, and end up hard of hearing. They also won’t hear game and nature, can’t join in conversations, and tend to take passive muffs off to listen… just when the person next to them fires a magnum with a muzzle brake. How can it be that I shoot next to people who have spent £4,000 on a rifle, £2,000 on a scope, drive a top-spec car, yet won’t spend £75 protecting their priceless and irreplaceable hearing? If that’s you, buy some now.

Perfect fit

When you shoot as much as I do, having a rifle that fits and handles well becomes a prerequisite. Try closing your eyes, then mounting your rifle (unloaded and in a safe direction) as if it were your favourite shotgun. If you don’t have a shotgun, sort it out, as it is your British birthright to possess one unless you are nuts… in which case you won’t be worrying about rifles. My point is that, when you open your eyes, you should be looking straight through the sights with good cheek weld, perfect eye relief and ready to acquire your target.

If instead you are looking at the back of the bolt and underneath the scope, then your stock is too low and your scope may be fitted incorrectly, or both. Good fit matters with rifles, as it does with shotguns, car seats and clothing – if it does not fit you will not be comfortable or optimal in performance. I notice that when I have to set the side of my jaw against a typical rifle stock comb to see through the scope it becomes uncomfortable, and notably quickly in larger calibres. If the comb can be set so I can acquire a perfect sight picture with my cheek fully engaged (shotgun style) then I can shoot optimally and comfortably.

Further advantage from a proper cheek weld and sight picture is that, while reloading after the shot, the rifle is firmly held and can be kept on target while the dominant hand swiftly cycles the bolt. In addition, proper cheek weld reduces perceived recoil and improves accuracy, which makes me wonder why so many rifles are so low in the comb. It seems that stocks are often still made as if someone might use open sights, even when these are not fitted to most modern rifles. Fortunately, the market is now providing some rifles with adjustable combs, which I believe are preferable to the older designs that often do not allow proper cheek weld.

The thrust of this article is simple – if you want to shoot better then you need to protect yourself from recoil and noise, ensure your rifle is fitted properly, and hold it firmly using the advice above. After that, shooting it to best effect will depend on proper training and practice. Over to you.

Related Articles

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

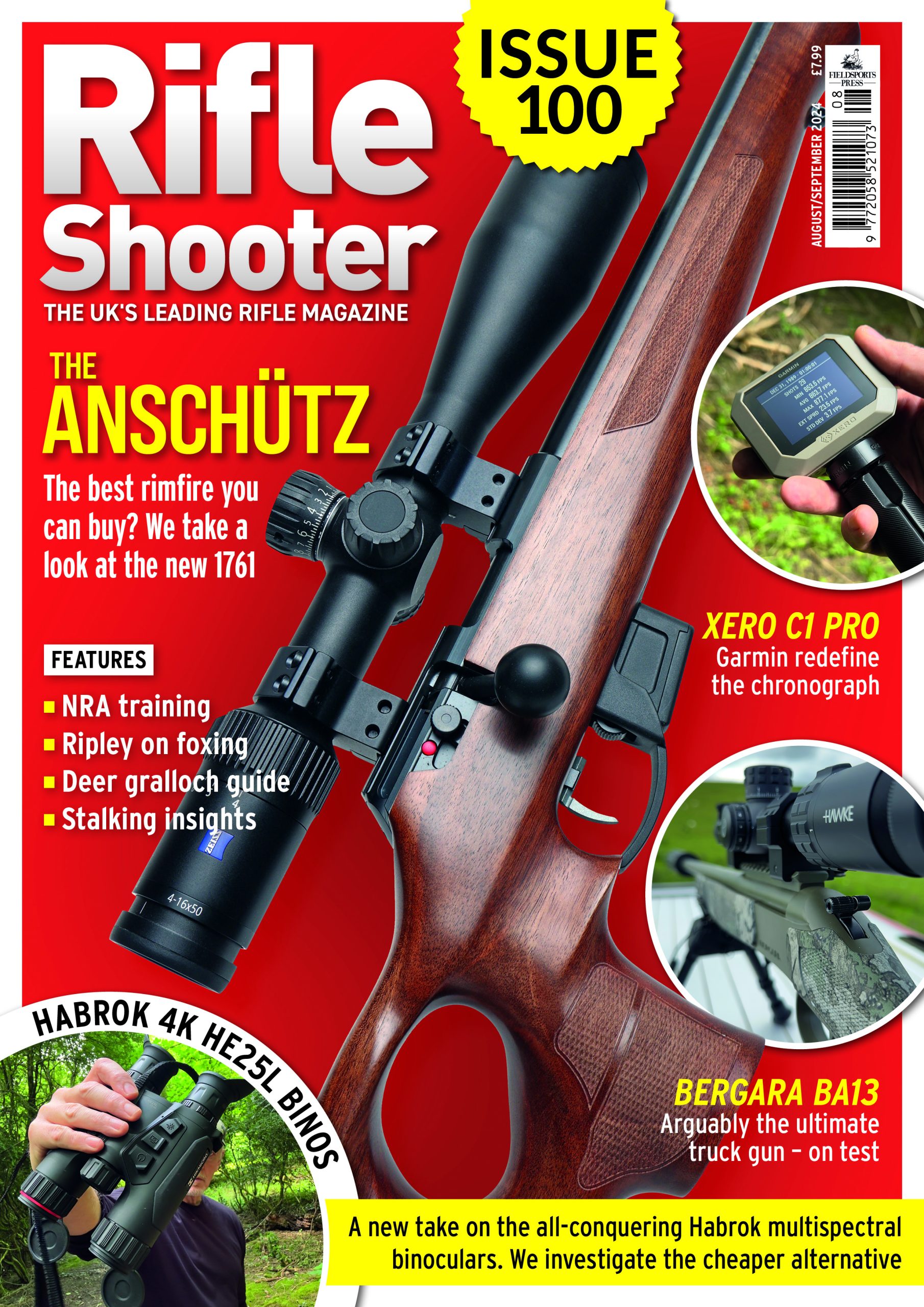

Subscribe to Rifle Shooter

Elevate your shooting experience with a subscription to Rifle Shooter magazine, the UK’s premier publication for dedicated rifle enthusiasts.

Whether you’re a seasoned shot or new to the sport, Rifle Shooter delivers expert insights, in-depth gear reviews and invaluable techniques to enhance your skills. Each bi-monthly issue brings you the latest in deer stalking, foxing, long-range shooting, and international hunting adventures, all crafted by leading experts from Britain and around the world.

By subscribing, you’ll not only save on the retail price but also gain exclusive access to £2 million Public Liability Insurance, covering recreational and professional use of shotguns, rifles, and airguns.

Don’t miss out on the opportunity to join a community of passionate shooters and stay at the forefront of rifle technology and technique.