Ulf Lindroth hunting wolves – Alberta, Canada

Would you like to appear on our site? We offer sponsored articles and advertising to put you in front of our readers. Find out more.

Ulf Lindroth travels to Alberta in Canada to hunt the most secretive and challenging quarry of all – the wolf

All animals are equal, right? Well, brace yourself – that may just be graffiti on a barn wall. When you catch the eye of a wolf, you’ll be startlingly, spine-chillingly aware that some animals really are a cut above the rest.

The life of the travelling hunter need never get dull. There are always new challenges. For the weary pilgrim of long hunting paths, with walls covered in trophies and perhaps a shortage of ideas, I have a suggestion: try wolf.

Now, you may already have shot one by chance on a moose or bear hunt; if so, lucky you. Most hunters who go north never see a single wolf. Certainly, they may hear wolves howl on some starlit night – they may even catch a distant glimpse – but they don’t usually get them in their sights.

The reason is simple; not only will the wolf match the senses of any other wild animal, but he will also be smarter than just about all of them. Then again, if you really want a challenge, the wolf may be what you are looking for.

Going into the wilds of Canada, Alaska or Siberia for a fair-winter wolf hunt may not be easy, but it will be different. It can also be tough. Not just long-days-on-the-trail tough, but tough in that unforgiving way – air almost too cold to breathe and sudden blizzards howling in from the Arctic. As likely as not, you won’t even get a shot at a wolf. But you will get adventure. And you may meet a quarry who is more than a few cuts above the regular animals (even the pigs).

No mistake

I got my first taste of wolves in 1996. That spring, fresh out of university, I left for British Columbia and worked for an outfitter through a hunting season in the Canadian Rockies. In retrospect, I blush when remembering how confident I felt about getting a wolf. The follies of youth…

In mid July we rode into the mountains with a string of packhorses. For weeks we cleared trails of wind-fallen trees and branches, and repaired camps. We scouted for game from the river valleys to the rugged peaks.

Seeing bears was commonplace – mostly black bears, but also some grizzlies. One or two of those meetings would make a tale of their own. But even if wolf tracks were just as numerous as bear tracks, no wolves made the mistake of showing themselves.

At the evening campfires, old Pat Yahey (a hunting guide of Cree ancestry) would tell grizzly stories for drama, but on the rare occasions that he spoke of wolves, he became reverent. Those stories were different. Like when his uncle once shot a wolf, only to have a pack enter camp and kill a horse the following night, presumably in revenge. Tall stories, most likely, but definitely good for a shudder in the flickering light of a fire.

Only on the day we rode out of the mountains did we eventually see wolves. Towards the end of that long day we had reached a lonely logging road. Pat and his wife, Killan, rode up front. Behind them followed 10 packhorses. I brought up the rear, and thus could do nothing when two wolves slowly strolled out on the road, just in front of Pat.

They looked him over for what seemed an eternity, but Pat never touched his rifle. As they trotted off, I realised that even if I had finally seen wolves, I still hadn’t seen them make a mistake; I never did. I just saw their tracks and heard the odd eerie howl from the timbered mountainsides. And I knew, someday, I had to outsmart one.

A long story

In the years that followed, I tried calling wolves in Alberta. It got me a new record for the coldest temperature I’d experienced (-45°C), a couple of answering howls, and one quick glimpse of two wolves at 400-plus metres. I went to Belarus to take part in an old-fashioned hunt with flag lines, but snow turned to rain and the hunt was a bust. I tried calling wolves in Idaho, with no success, and I kept an eye out for them on other hunts in Canada, USA and Latvia… nothing.

In 2010 I went back to Alberta with fellow hunter, Anders Eriksson. This time I felt the stars were aligned. Our outfitter, Sven-Erik Jansson, had managed to get us the chairman of the Alberta Trappers’ Association and renowned wolf expert, Gordy Klassen, as a guide. In his own words, Gordy had quit guiding, but made an exception because he owed Sven-Erik. His help made a world of difference.

Gordy told us he had been maintaining two bait sites out of his trapping cabin at Sardine Lake. They had been well stocked with road-killed moose and deer for weeks. Just a couple of days before our arrival, Gordy had filmed seven wolves on the bait that Anders would sit and watch.

The plan was simple: the baits were placed on the ice of two different lakes; their main purpose was to attract ravens, which would then attract travelling wolves, and that would allow for daylight hunting. Since we were already in March, wolves were more than likely to move a lot in daylight.

The blinds were made of poles and tarpaulins and placed some 230-240m away from the baits to avoid detection. They stood under shading timber, taking into account the prevailing wind. Our job was to sit there, from before dusk and for the following 11 hours, for 10 days straight. By then, the wolves should have paid us a visit… maybe, at least.

Gordy was as superstitious about the wolves as old Pat Yahey: ”You’ll never get a wolf unless you get the stress out of your system,” he told us with a very straight face. ”You won’t get one if you don’t deserve it.”

In awe

And perhaps I finally did. Anyway, at around 3pm on the second day, after some 20 hours in the blind, I saw a sight I am not likely to ever forget – a large black wolf.

It looked far bigger than I had imagined. Its legs were longer and it moved fast over the ice. Too fast, I thought. As it passed the bait and kept going, I nearly panicked.

Still, my plan was simple and I had practised the moves. And I was in luck. As I stabilised the forestock on a big glove on top of the window frame, and snuggled the shooting stick in under the butt of the stock, the wolf turned back to the bait.

Almost playfully, it chased a few ravens away. In my scope, I saw it look at them as they circled just above him and made irritated noises.

Never did I see such eyes on a game animal. There was an arrogantly playful look in them as they followed the nearest raven. They were alert, confident and challenging. I was awed. And then I fired.

Howling in the night

The wolf ran 90m before it collapsed. As it fell, I was immensely relieved. For some reason I also felt more sentimental than I ever had shooting any other game animal. When it came in across the ice, it did so convinced that it was at the top of the food chain; and perhaps it was meant to be. I was happy, but also humbled.

I shot another wolf the following day. It was a large grey male, leading a pack of six wolves. It was also impressive, but in a different way; it struck me by its alertness.

The pack came in over a kilometre of ice, but even before they reached the bait some sixth sense told the alpha male that something was wrong with a specific spot on the ice. It went straight to where we had loaded the first wolf on the snowmobile sled. No tracking, nothing. Just straight to the spot.

I shot that wolf at 330m as it belly-crawled to have a sniff at our tracks. It didn’t have the arrogant look of the first wolf, but it did drive home how hard it is to fool these animals.

Anders waited his 10 days without ever seeing a wolf, but they gave us all a final farewell. At 3am on the last night at Sardine Lake, a quiet but urgent Gordy woke us up. On the nearby ice, wolves were howling. We could not see the pack, but their wild voices filled the night.

I’ve heard lions roar; I’ve heard angry bears; but for sending chills up my spine, give me wolf howls on a night in the frozen wilderness.

My affair with the wolf may confuse me at times – I don’t always know if I’m his equal or not. But, if you want a challenge, I know he won’t disappoint you. And, whenever you take one, you will give the simpler brutes a much-needed break.

Related articles

AN ICELANDIC SAGA

A relentless search across Iceland’s volcanic landscapes takes Simon K Barr to the ultimate prize – a mature bull reindeer and an unforgettable hunting experience

By Time Well Spent

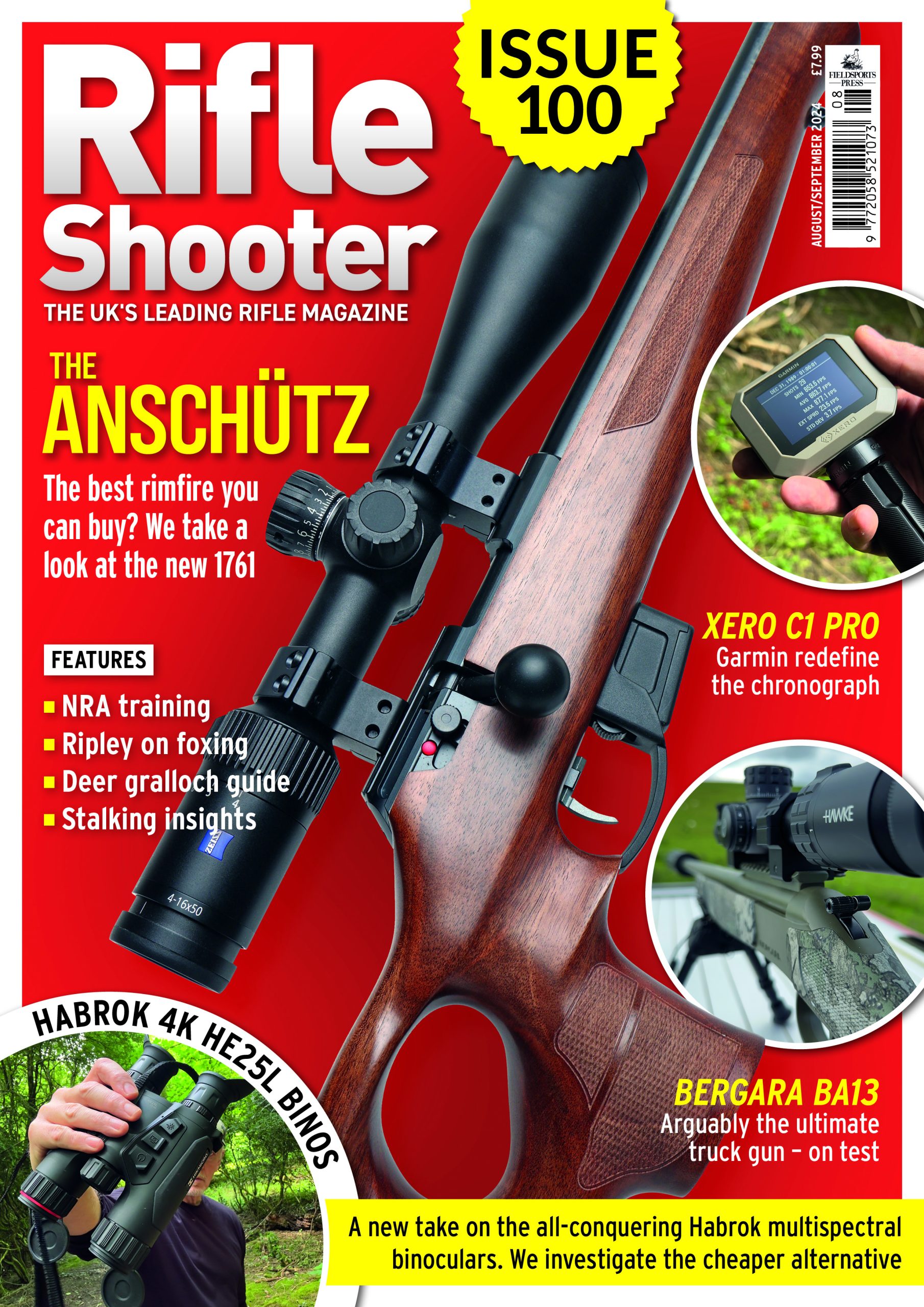

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

Subscribe to Rifle Shooter

Elevate your shooting experience with a subscription to Rifle Shooter magazine, the UK’s premier publication for dedicated rifle enthusiasts.

Whether you’re a seasoned shot or new to the sport, Rifle Shooter delivers expert insights, in-depth gear reviews and invaluable techniques to enhance your skills. Each bi-monthly issue brings you the latest in deer stalking, foxing, long-range shooting, and international hunting adventures, all crafted by leading experts from Britain and around the world.

By subscribing, you’ll not only save on the retail price but also gain exclusive access to £2 million Public Liability Insurance, covering recreational and professional use of shotguns, rifles, and airguns.

Don’t miss out on the opportunity to join a community of passionate shooters and stay at the forefront of rifle technology and technique.