The countdown is on for The British Shooting Show – book tickets online today and save on gate price!

Trophy or management?

What keeps us hooked on deer stalking isn’t just pulling the trigger—it’s the quiet challenge, the connection with the land, and the unpredictable dance between hunter and deer. In this reflective piece, the author explores the ethics, emotions, and encounters that shape every outing in the field.

Every time I go out deer stalking, the objective is the same: to take a deer. But the fact that it doesn’t happen every time is what keeps us coming back. The challenge lies in pitting your wits against a wild animal that’s finely tuned to its environment.

You often hear stalkers say, “It’s not about pulling the trigger.” That’s true. Every stalker I’ve met genuinely enjoys spending quality time in the countryside.

A Difficult Discussion

I recently got into a conversation with a tenant renting a house on the farm where I shoot. I was riding down a farm track on a quad bike, with a red hind and its calf in the trailer. He wasn’t pleased to see them. Earlier that day, he had been photographing those same deer on the higher ground.

He asked how long I had been stalking there, how often I would return, and how many I planned to take.

This is a new patch for me, and the deer numbers are high. The oak woodland shows clear signs—few trees have escaped being nibbled and many have started growing like coppice. The herd needs reducing, and the two deer I had taken were a strong start.

I explained my plan: to take a mix of young, old, and middle-aged deer. We took time to talk things through, and he left with a better understanding of my role.

Trophy or Management?

In the same group, I’d spotted four stags. One met my criteria, but no clean shot presented itself. I couldn’t help thinking—what if I had driven down that lane with the stag in my trailer instead?

Chances are, he had photographed that very stag. As soon as an animal can be identified, people tend to anthropomorphise it, which quickly leads to accusations of trophy hunting. When an animal has antlers, it becomes personal for some people. And yet, female deer rarely provoke the same reaction.

Though I’m proud of my work, I’ll carry a tarp next time—no need to be provocative.

I used to live in a rural house where fallow deer wandered through the garden. I recognised individual bucks and does and often hoped they’d stick around for years. I wouldn’t have challenged a stalker shooting next door, though I quietly hoped they’d spare the ones I knew.

Last summer, a friend invited me to take a “unicorn” roe buck from his land. He wasn’t truly a unicorn; one antler had snapped off above the coronet. He wasn’t old or remarkable but fitted the ground’s management plan. I accepted the invitation, knowing it might take a while.

A Promising Start

My friend believed the buck would stay in the area. The topography and the large watercourse flanking the ground made it ideal. He kept checking, and by late August, the buck was still about.

We went out on a warm morning. On our way to the high seat, a doe crossed our path, delaying us. Thermals revealed plenty of does and kids, but no bucks. As the day warmed, dog walkers, cyclists, and runners arrived. We called it off.

Though frustrated, my friend understood. I felt oddly satisfied. There’s no real joy in a quick success. The morning had been beautiful, just watching deer.

I missed the evening outing, but returned a week later. We sat over a meadow with long grass and young trees. With my back to a house, I scanned the field. A heat signature appeared. It looked promising.

After an hour, the shape moved. A roe doe stood and disappeared into the woods. Forty-five minutes later, we heard movement again. Another doe emerged with a kid and wandered off.

As the sun dipped, roe deer emerged from the field margins—around 15 of them. A larger shape followed. Through the thermal, it looked like a buck.

We began our approach, but with so many does in the way, darkness beat us to it.

Holding Out for a Chance

Next morning brought more does and kids, but no bucks. In the afternoon, we returned and sat in a high seat across from where we’d seen the buck the night before. We had three hours of light left.

Geese landed nearby, oblivious to us. Dog walkers roamed the paths, but the deer remained calm. They briefly dipped into cover and came back out again.

About an hour in, I saw two shapes moving along the hedge. Ten minutes later, a doe appeared—followed by the unicorn. He was 200 metres away, but the farm sat directly behind him.

We stayed put. Moving would have spooked the geese. The doe slowly walked parallel to us, drawing the buck closer. But cattle behind them made it unsafe to shoot. I picked up my camera instead.

They moved steadily down the field, eventually aligning with another house. With 45 minutes of light left, we made our move.

The Final Move

We dropped down the hedge and reached another high seat, hoping to catch them 120 metres out with a safe backstop. At first, I couldn’t see them. Then my host spotted them behind a bale. They were on the move, regularly stopping to listen. The moment came. The buck stepped into view in front of a bale. As the two separated, I took the shot. He dropped instantly. That buck gave me good meat, an unusual skull, and a lasting memory.

But I keep thinking—was that a trophy hunt? Anti-hunting voices often use “trophy hunting” to describe any antlered animal taken, regardless of the animal’s age or purpose. Oddly, they don’t seem to mind when we shoot does. It’s a strange world we live in.

Deer stalking is not only a traditional practice but a vital component of population control and conservation, as outlined in our internal overview on Deer stalking.

Related Articles

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

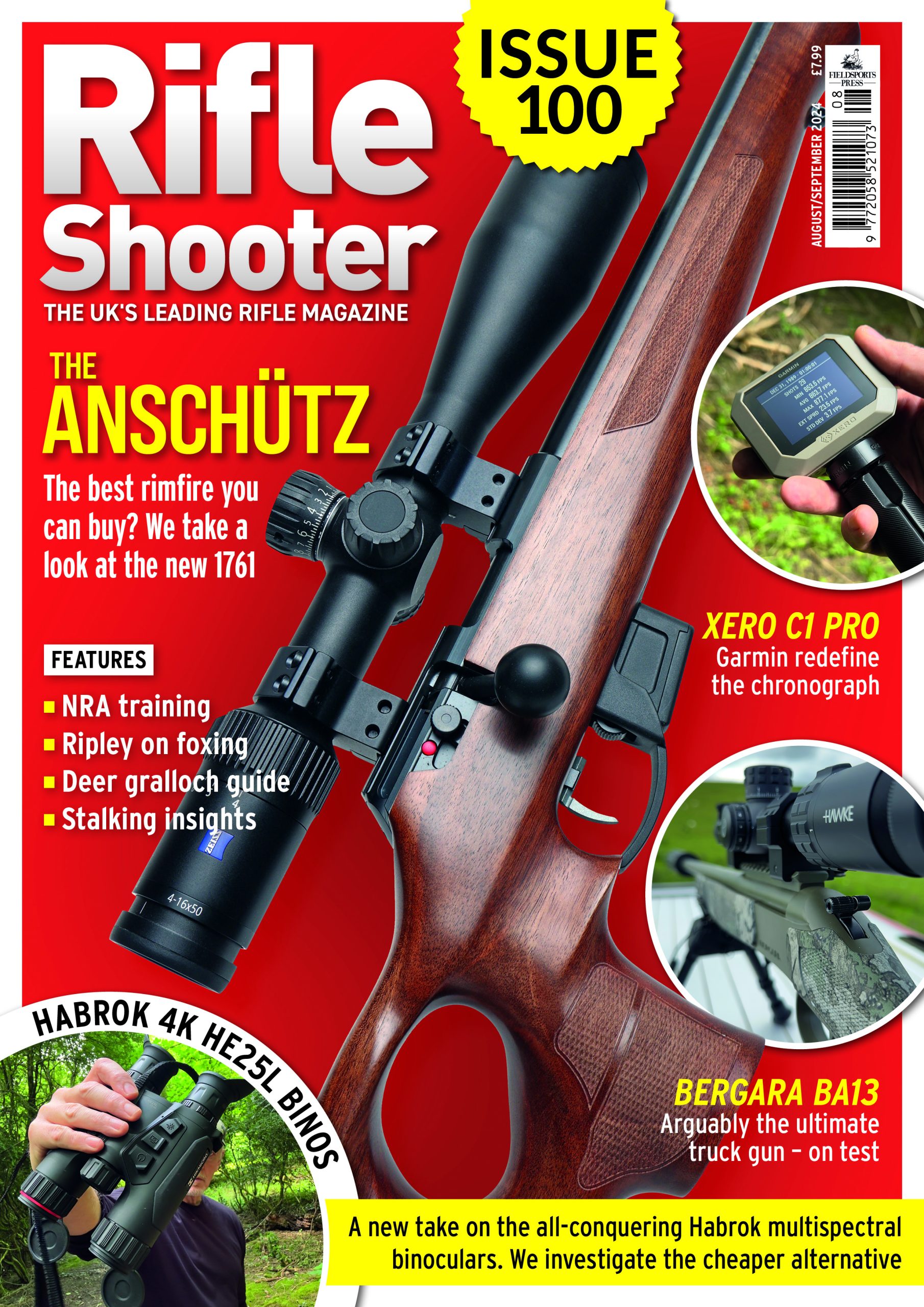

Subscribe to Rifle Shooter

Elevate your shooting experience with a subscription to Rifle Shooter magazine, the UK’s premier publication for dedicated rifle enthusiasts.

Whether you’re a seasoned shot or new to the sport, Rifle Shooter delivers expert insights, in-depth gear reviews and invaluable techniques to enhance your skills. Each bi-monthly issue brings you the latest in deer stalking, foxing, long-range shooting, and international hunting adventures, all crafted by leading experts from Britain and around the world.

By subscribing, you’ll not only save on the retail price but also gain exclusive access to £2 million Public Liability Insurance, covering recreational and professional use of shotguns, rifles, and airguns.

Don’t miss out on the opportunity to join a community of passionate shooters and stay at the forefront of rifle technology and technique.