The countdown is on for The British Shooting Show – book tickets online today and save on gate price!

Sniper Skills: The New Normal

As Ireland extends its stag hunting season, Will O’Meara considers the implications of the longer period for conservation and deer management

It’s a new season – or at least an addition to the old one. Yesterday stags were out of season; today they are in season. Recent changes to legislation in Ireland means that male deer can now be hunted in an open season for nine months of the year, from August to the end of April.

Females also see an extended season. The old season ending on the last day of February has been extended by a month to the last day of March.

My initial feeling about the stag season almost doubling in length is one of concern, but I temper this with the hope that it will give hunters the freedom to manage their areas in a responsible manner, reducing damage to crops and keeping deer numbers at a tolerable level. We all know that there are some who will act with short- sightedness and all we can do is act with sense in our own areas and caution them on their folly.

Through my articles over the years I am probably best known for hunting sika and red/sika hybrids in the mountains of Wicklow, but that wasn’t always the way. For many years I mostly hunted fallow. During that time I was always drawn to the mountain and I spent a fair portion of my time in the hills of Tipperary. The deer population there wasn’t like Wicklow, but with hard work and dedication I could manage an average of one deer per day.

In all those years of hunting in Tipperary I never saw a decent fallow buck. I probably put in 40 days a year over seven years and the only time I would see any bucks was during the rut. Even then they would stick to the heavy timber, deeply hidden from view, with only their deep guttural croak to guide you into their location.

Near the end of February you might catch a glimpse of some young bucks out feeding but the old boys were never with them. There were a number of reasons for this, I think. This area was once for good fallow bucks but all that changed just a couple of years before I started hunting there. I was a member of a syndicate, a group of about 10 like minded hunters who all pitched in to lease a number of forests in the area. We also gained deer-hunting permissions from local landowners and helped out with predator control during lambing season. These forest leases were for a period of five years and the group that leased them before us hit them very hard for bucks. That, coupled with heavy poaching at night, had brought us to where we were.

I can’t help but feel that a nine- month season for male deer will bring us to a similar situation in other areas. The principles of deer management are aimed at controlling deer in an area to ensure that their numbers don’t go out of control and are tolerable to competing interests in the area, such as farming and forestry. There is nothing better than when this is done in a manner that delivers a balanced age profile in the population, allowing the best of stags to mature and pass on their genes and then be killed before they decline into old age and poor condition.

It also strikes me that focusing on male deer in an effort to reduce numbers is a flawed approach. The females are the ones that produce the calves, so if we truly want to reduce numbers in an area then they are the ones that need culling. Again balance is required, as is a skilled eye and a disciplined approach, to ensure we don’t leave young orphan calves to fade away

without maternal care. The best we can hope for is that deer stalkers take this season extension and use it to reduce numbers where required and be sensible about it.

During March I cull females and yearlings in high population areas, and now that the longer evenings of April are here I get out now and again for an evening stalk. On one such evening during the first week of April I planned to hunt the fringe of a forest, where the timber meets the mountain.

It was an uphill pull all the way from my start point. I stopped periodically to glass ahead and a few hundred meters in I was rewarded with the view of a pricket grazing. The wind was full in my favour. I lined up some trees between the young deer and myself and started my approach, being – careful not to bump into any other deer between me and the deer I’d spotted.

The lie of the land meant I could get within 80m with relative ease. Once there, I knelt down and glassed methodically. With confirmation that the pricket was alone, I started my crawl forward, but I only got 10m before I realised that was as far as I could go. The ground started to fall away sharply into a deep gully, so my firing position was to be prone and slightly downhill.

The pricket was unaware but he exhibited that common deer behaviour – stopped, paused, stared… continued feeding. I silently drew back the Tikka’s bolt – not all the way, but far enough to allow me to slide the next Sako mini-missile into the chamber. It wasn’t that I needed the extra ammunition capacity in this instance, but top loading an extra round into the chamber rather than racking one from the magazine is very quiet and would allow me to stay undetected.

I have learned through my guiding experience that it is often in the final moments of a stalk that deer are alerted to your presence. This is often due to rushing into a firing position, fearing the deer will be gone. Also rushing the loading of the rifle can create a noise that is an alarm bell to the deer. This I believed, is often a reflection of stress. When we encountered stressful situations our ‘lizard brain’ takes over and tells us to get done with this stressful situation as quickly as possible. But if you understand this and recognise

when it is happening, you can take a deep breath and calmly and quietly go through the preshot and shooting process.

In this instance I was set up and ready to shoot undetected. The only time pressure was the setting sun, but again I was getting ahead of myself. I patiently waited for the pricket to present and when he next stopped I focused on trigger control. The shot placement was as intended and as I watched the pricket drop in my scope the shot echoed through the silence of the

evening. I unloaded and went straight in for the follow up, as I always do with a neck shot.

The pricket was dead on arrival, the impact having completely severed the spine at the head/neck junction and would have simultaneously delivered a devastating shock to the brain. I

gralloched and inspected the vitals, making the most of the evening sun, and then took a moment to appreciate the view below. The tranquillity of sunset had a quiet magic to it that fuelled the soul.

Enough of all that. I got the drag rope on and got my load across the steep gully. From there it was all downhill – a blessing in the fading light and rough ground. I glanced back and spied a hind and calf on the skyline observing my descent. I smiled and wondered in that moment if it was a feeling deeply ingrained in our genes to be glad to see deer there for another day’s hunting? If so I was glad it was and could only hope that such thinking is applied to the hunting of stags through this new extended season.

Related Articles

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

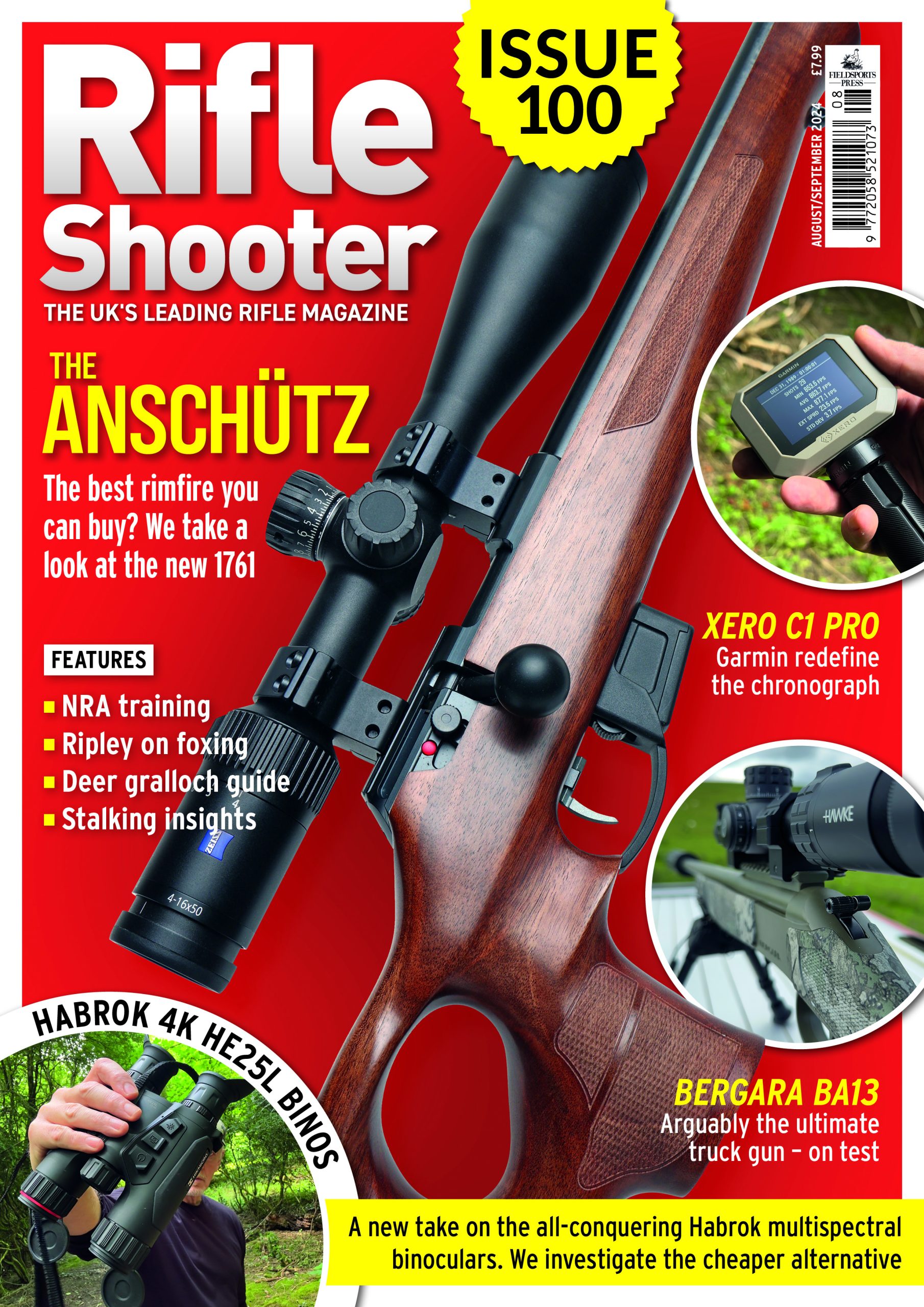

Subscribe to Rifle Shooter

Elevate your shooting experience with a subscription to Rifle Shooter magazine, the UK’s premier publication for dedicated rifle enthusiasts.

Whether you’re a seasoned shot or new to the sport, Rifle Shooter delivers expert insights, in-depth gear reviews and invaluable techniques to enhance your skills. Each bi-monthly issue brings you the latest in deer stalking, foxing, long-range shooting, and international hunting adventures, all crafted by leading experts from Britain and around the world.

By subscribing, you’ll not only save on the retail price but also gain exclusive access to £2 million Public Liability Insurance, covering recreational and professional use of shotguns, rifles, and airguns.

Don’t miss out on the opportunity to join a community of passionate shooters and stay at the forefront of rifle technology and technique.