Until the late 1970s, few if any of the spring airguns on the UK market were capable of achieving 12 ft.lbs., or anywhere near it – unless they were dieseling – and electronic chronoscopes were not available, so keeping your springer legal was simply not an issue for most. Then, in fairly rapid succession, Feinwerkbau launched the ‘Sport’; Original their Model 45; Weihrauch the HW80; and Webley the Vulcan – all break-barrels, and all capable of exceeding 12 ft.lbs., so for the first time, keeping muzzle energy under 12 ft.lbs. became a very real consideration, especially for those who enjoyed tinkering with their rifles.

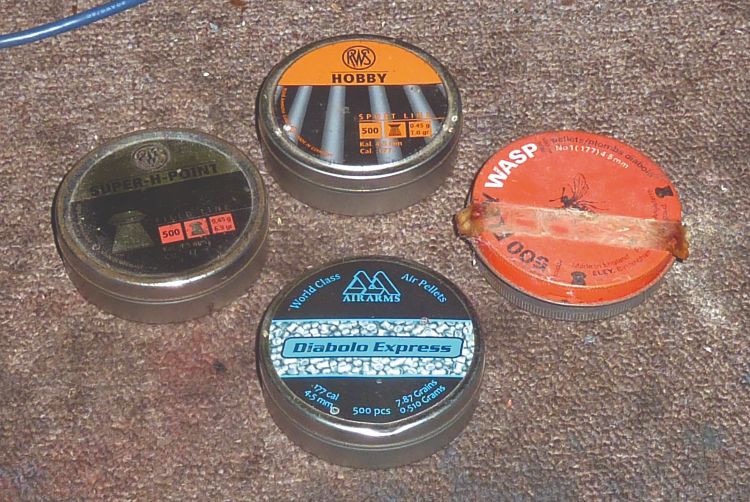

Then, as now, there was no standard test pellet for checking muzzle energy, and so it was good policy to ensure that your springer was safely legal with whichever pellet gave the highest muzzle energy, but the question was, which pellet? In the majority of 1980’s spring/piston air rifles, the pellet that gave the highest muzzle energy was the RWS Hobby, so that effectively became the de facto test pellet.

The reason that the Hobby usually gave the highest muzzle energy from 1980’s springers was due to a combination of the pellet’s light weight (6.9gn in .177, 11.9gn in .22), hard antimony/lead alloy and consequent high start pressure (~600psi in .177), and the usually fairly short strokes of the springers themselves. In short, by the time the pellet started to move, the air was highly compressed, and the combination of that, plus the light weight of the pellet, and the fact that many, if not most, of the springers at the time were dieseling, gave it blistering acceleration in the barrel.

LOW BC

LOW BC

The .177 Hobby’s light weight almost always gave the fastest muzzle velocity, and you could tune your rifle to give a safely legal 11.5 ft.lbs. and have the pellet leave the muzzle at 866fps.

Unfortunately, the flat-head design gave high drag, which in combination with the light weight, gave the pellet a very low Ballistic Coefficient (BC), which meant that it shed velocity rather more quickly in flight than conventional round-head pellets, and made it more susceptible to wind drift, which in turn, limited its useful range.

For indoor target shooting, the Hobby was a great pellet, but less so in the great outdoors. The outside air is rarely anything approaching still, and air movement is rarely consistent in intensity and direction, so wind drift limited accuracy, and in real-world conditions, the Hobby was a 25-yard (or near offer) pellet. That said, the high drag that slowed the pellet so quickly in the air also slowed it more quickly in the cranium of a rat, rabbit or grey squirrel, and that is exactly what the pest controller needs.

MAKING AN IMPACT

If a pellet with 10 ft.lbs. of kinetic energy travels 1” through a substance before coming to a halt, the impact force is 10 x 12, or 120 pounds of force (lbf), and if the pellet comes to a halt in half in inch, the impact force doubles to 240 lbf. That helps give clean kills, provided the pellet hits the correct spot, making the Hobby a superb short-range, pest-control pellet.

Another 6.9gn pellet of the 1980s was the Eley Wasp, at the time manufactured and to a very high standard by Eley. Light weight was the only thing that the Wasp had in common with the Hobby, because it was a round-head pellet, and so had a far superior BC and maintained velocity in flight much better. It was also far less susceptible to wind drift, and capable of much longer range accuracy, so was a superb pest control pellet at ranges well beyond 25 yards.

SOFT ALLOY

SOFT ALLOY

The two great lightweight pellets of the 1980s, the Hobby and Wasp, were both made from a lead alloy with a high antimony content, which made them very hard, and was responsible for their high start pressures that so suited contemporary springers, but today, we have lightweight pellets made from far softer alloys, with correspondingly low start pressures – such as the 7.3gn Falcon Accuracy Plus, for example.

I measured the start pressure of the .177 Falcon Accuracy Plus in my HW77 at just 120psi, making it a very good choice for use in springers with short strokes that typically give low muzzle energy figures with harder and/or heavier pellets, because it tends to give not only higher muzzle energy, but also a decent muzzle velocity.

Unlike the Hobby in 1980’s springers, the Falcon Accuracy Plus rarely delivers the highest muzzle energy in today’s springers, because they have sufficient stroke length to get more energy from heavier pellets, such as the 7.9gn pellets made by JSB and sold as Air Arms Express.

VERY HARD

Today, we have a growing variety of pellets made, not of lead alloy, but from alloys of far lighter metals, typically tin and zinc, making them much harder than the lead alloys of 1980’s pellets, and also very much lighter in weight. The weight of a pellet, in relation to its cross-sectional area (the sectional density), has a bearing on its BC, and all other things being equal, lighter means lower BC, greater velocity loss in flight, and increased wind drift susceptibility.

My only indirect experience of non-lead pellets was when I was sent a springer to review that unbeknown to me, had been used with non-lead pellets, and the accuracy of which with conventional lead pellets was abysmal. Knowing that the rifle in question had a barrel from a manufacturer known for the accuracy of their products, I gave the barrel a good scrub with a phosphor bronze brush, and after a goodly number of shots with lead pellets, accuracy was slowly restored. I found out later that non-lead pellets had been used in the rifle before it was sent to me, and as a consequence, I am in no great rush to try them in any of my airguns.

Sooner or later, I am aware that I will have to investigate non-lead pellets, but this article will confine itself to lightweight lead alloy pellets.

SPRINGERS

SPRINGERS

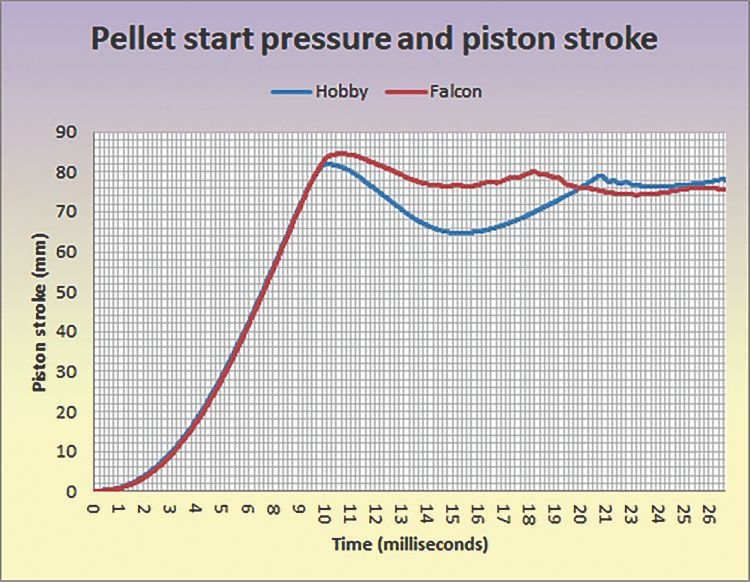

Let’s look at how the .177 Hobby and Falcon Accuracy Plus affect the springer shot cycle. I measured the Hobby start pressure at no less than five times that of the Falcon Accuracy Plus, at 600psi verses 120psi, and this has a fundamental effect on the shot cycle.

The Falcon Accuracy Plus starts to move when the piston is around 79% into the available stroke, at which the air has gained around 4 ft.lbs. of internal kinetic energy, and the air pressure places a force of 2.7lbf on the pellet, so the pellet initially accelerates fairly gently. In contrast, the Hobby stays stubbornly in the breech until the piston has travelled 93.5% into the available stroke, when the air has gained nearer 9 ft.lbs. of internal kinetic energy, and the air places a force of 14.5lbf, so the pellet’s initial acceleration is very fast.

The fact that the Falcon Accuracy Plus starts to move so much earlier, reduces the cylinder air pressure at any given piston travel point beyond pellet start, so the piston travels a little further. In fact, in one of my .177 TX200s I found the compression stroke to be 84.5mm, against the 82mm stroke with the Hobby. Of course, this means that the rifle recoils a bit further with the Falcon Accuracy Plus, but the difference is just 0.14mm, and there is no way anyone would be able to tell which pellet was in use just from the primary recoil displacement.

Because the Falcon Accuracy Plus is being accelerated for longer, it produced muzzle energy of 10.9 ft.lbs. in the test rifle, against 10.71 ft.lbs. for the Hobby, so the Hobby is most definitely not the pellet to test to ensure that a modern springer is safely legal, and that honour usually goes to the 7.9gn Air Arms Express with nearer 11.4 ft.lbs., or the 8.4gn, depending on the rifle and how it is set up.

The peak cylinder pressure with the Falcon Accuracy Plus worked out at 1,264psi, against 1,259psi for the Hobby, suggesting that, unlike its 7.9gn and 8.4gn siblings, which both gave higher muzzle energy, the Falcon was a tad too far up the barrel at piston bounce to take full advantage of the higher peak cylinder pressure; the Hobby wasn’t far enough up the barrel at the end of the compression stroke, and that it consequently wasted energy in greater piston bounce. By way of comparison, 8.4gn Air Arms Field generated a peak pressure of 1,151psi for a muzzle energy of 11.3 ft.lbs.

PCPs

The relatively low energy efficiency of heavier pellets in springers is to a large degree dictated by the very short duration of the air pressure pulse, but the pressure pulse in a PCP obviously persists for far longer, long enough, depending on the valve opening duration, to keep accelerating heavy pellets the full length of the barrel, which in a nutshell explains why heavier pellets tend to give higher muzzle energy in PCPs.

Given the generally higher muzzle energy with heavier pellets, the sole advantage of light pellets to a PCP user, in our power restricted market, is their higher muzzle velocity for any given muzzle energy, which means they fly flatter, so the user needs to aim off less outside the point blank range (PBR). Whether or not this is a genuine advantage in real-world shooting is debatable; in HFT, which involves using different reticle aim points according to range, and also aiming off to allow for the effects of wind, the vast majority of competitors use 8.4gn or heavier pellets, which have a better BC and tend to be less affected by wind drift, in my experience, and only a handful opt for light pellets.

EXTERNAL BALLISTICS

Many people seem to subscribe to the beguiling logical theory that lighter pellets will be blown off course more than heavy pellets, and use heavier pellets because of it, but that is plain wrong. A cross wind does NOT blow against the side of the pellet. However, there’s no getting away from the fact that if two pellets are exactly the same shape, then the lighter one will have the lower sectional density and the poorer BC, shed velocity in flight faster. and be more wind susceptible, against which, the lighter pellet will usually have the higher muzzle velocity. So, which is better in the wind, light or heavy?

Ballistician Miles Morris came up with a very simple guide to indicate how well a pellet will resist wind drift, and it is to multiply the muzzle velocity by the ballistic coefficient, and the higher the resultant number, the better the pellet will resist wind drift. The only way to know which pellet will best resist wind drift when shot through your own gun is to test the muzzle velocity, find the BC, and do the calculation.

VERDICT

VERDICT

My go-to rifle is my .177 TX200, which in its current state of tune gives a muzzle velocity of ~780fps with 8.4gn pellets, and not only a very useful trajectory, but an exemplary recoil cycle and the very best accuracy. If my main springer happened to struggle to get near 10 ft.lbs., then I would definitely try lighter weight pellets, provided I could find one that gave the accuracy I need, to gain a better trajectory.

Because .22 pellets have much lower muzzle velocities than their smaller siblings, lighter pellets can give a more useful trajectory. The .22 Hobby, at 11.9gn, would give a muzzle velocity of 649fps at a safe 11.4 ft.lbs., whilst the Falcon Accuracy Plus would give a muzzle velocity of 619fps at the same muzzle energy, and the 14.4gn Superdome would give 599fps.

The bottom line, though, is that accuracy trumps any other aspect of a pellet’s performance, and tempting though the trajectory of light pellets may be, I would always choose whichever pellet gave me the best accuracy in any rifle.